The movement for housing preservation strategies thus far has focused primarily on the preservation of affordable rental housing because while rental as a share of all housing stock has decreased over the past several years, so have real incomes. This has resulted in supply gaps for rental housing.

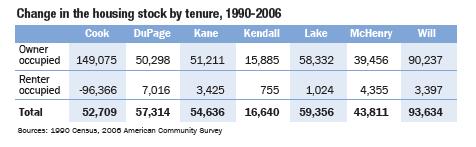

Rental housing has decreased as a percentage of national housing stock since 1990. Conditions in northeastern Illinois run parallel to national trends. Between 1990 and 2006, the seven counties in northeastern Illinois – Cook, DuPage, Kane, Kendall, Lake, McHenry, and Will - experienced a 7.5% decrease in rental housing units while owner-occupied housing units increased by 28.3%. Cook County alone has lost 96,366 rental units, while the collar counties witnessed a slight increase in rental housing since 1990 (see Table A below). Cook County's share of the region's rental housing decreased from 80.4% to 77.8% between 2000 and 2006. The combined increase in rental housing in the collar counties was not enough to compensate.

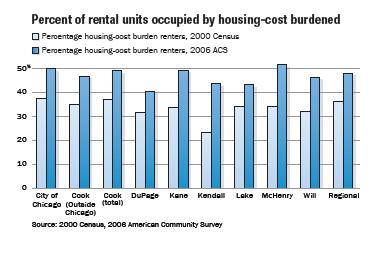

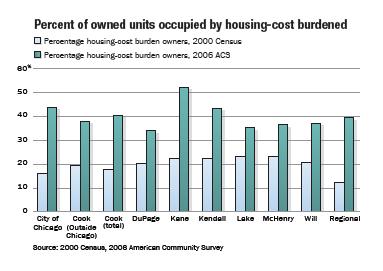

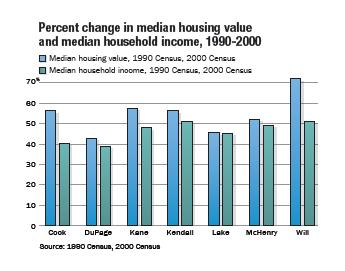

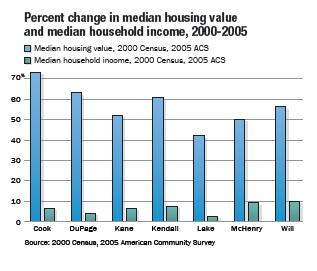

Meanwhile, the number of households spending 30% or more of income on housing has increased since 2000, which can be attributed to declining household income and increasing housing costs over the same time period. Housing experts refer to these households as "housing cost burdened." In partnership with the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus, Chicago Metropolis 2020 published an analysis of the supply and demand for housing at different price points in 2005. Results indicate that the number of families stressed by excessive housing costs is projected to grow from 730,000 to 870,000 across the region in 2030 based on current conditions and trends (Chicago Metropolis & Metropolitan Mayors Caucus, 2005).

Responding to the decrease in rental housing stock, initiatives to prevent further decline are underway across the nation. In 2007, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation increased a commitment to "preserve and improve at least 300,000 units of affordable rental housing across the country" by a factor of three to $150 million (MacArthur Foundation, 2007).

Acknowledging the urgent need to reverse a downward trend in affordable rental housing stock, the Urban Land Institute assembled the Preservation Compact of Cook County in 2005 with support from The MacArthur Foundation (Urban Land Institute 2007). Preservation Compact analysis concluded that the demand for affordable rental housing in Cook County alone will outpace supply in the year 2020 by almost 38,000 units (DePaul University, 2006).

We shall now address how housing preservation impacts northeastern Illinois and why housing preservation is a worthwhile strategy to implement.