This appendix provides information that can be useful to municipalities that are interested in evaluating parking strategies and creating new policies.

Parking Management Appendix

Sep 15, 2013

Appendix

Parking Pricing Techniques

Todd Litman's Parking Pricing techniques offer a succinct version of many strategies presented in this paper (2008):

- Wherever possible, charge motorists directly for using parking facilities. If parking must be subsidized, offer comparable benefits for use of other travel modes, such as Cash Out payments.

- Manage and price the most convenient parking spaces to favor priority users. Charge higher rates and use shorter pricing periods at more convenient parking spaces (such as on-street spaces, and parking near building entrances) to increase turnover and favor higher-priority uses. Prime spaces suitable for short-term use should generally be at least twice as expensive per unit of time as less-convenient spaces suitable for longer-term uses. For example, in a central business district charge 25¢ for each 15-minute period with a two-hour limit, while at the fringe charge $4 per day. The ratio between short- and long-term spaces may need occasional adjustment to optimize use.

- Use variable rates that are higher for peak locations and times. Apply performance-based parking prices, which means that prices are set so that about 15% of parking spaces are unoccupied during peak periods (Shoup, 2006). For example, charge $1 per hour for parking downtown during weekdays, $0.75 per hour for parking downtown during evenings and weekends, and $0.50 per hour for parking in other locations.

- Improve Pricing Methods to make Parking Pricing more cost effective, convenient and fair. For example, use electronic pricing systems that accommodate various payment methods and rates, and allow motorists to pay for just the amount of time they will be parked. For short-term parking charge by the minute rather than by the hour, and for long-term parking charge by the hour rather than by the day or month.

- Avoid discounts for long-term parking leases (i.e., cheap monthly rates).

- Use a progressive price structure in more convenient spaces to favor short-term users. For example, charge $1.00 for the first hour, $1.50 for the second hour, and $2 for each subsequent hour.

- To increase revenues, expand when and where parking is priced rather than raising rates at existing priced facilities. This is more efficient and equitable, reduces spillover problems, and usually raises more total revenue.

- Set parking prices to equal or exceed transit fares. For example, set daily rates at least equal to two single transit fares, and monthly rates at least equal to a monthly transit pass.

- Minimize discounts for long-term parking passes. For example, set daily rates at least 6 times the hourly rates, and monthly rates at least 20 times daily rates. Even better, eliminate unlimited-use passes altogether. Instead, sell books of daily tickets, so commuters save money every day they avoid driving.

- Eliminate early-bird discounts.

- Unbundle parking, so people who rent or purchase building space can choose how much parking is included.

- Avoid excessive parking supply. Use Parking Management to encourage more efficient use of existing parking facilities and address any spillover problems that result from pricing.

- Encourage businesses to price, cash out and unbundle parking by providing rewards to those that do, legislating it, or by imposing special property taxes on un-priced parking.

- Unbundle parking from housing, so apartment and condominium residents pay only for the parking spaces they need (Location Efficient Development).

- If parking must be subsidized, use targeted discounts and exemptions, rather than offering free parking to everybody. For example, to subsidize customer parking, allow businesses to validate parking tickets or provide free parking coupons to customers. To subsidize parking for people with low incomes or disabilities, provide discounts directly to those individuals.

- Tax parking spaces, and encourage or require that this cost be passed on to users. Reform existing tax policies that favor free parking. For example, tax land devoted to parking at the same rate as land used for other development.

- Charge a tax on curbcuts comparable to potential revenue foregone had the same curb area been devoted to priced on-street parking. This would encourage property owners to minimize the number and width of curb cuts, through access management and consolidation of driveways and parking facilities, which helps improve traffic flow and create more pedestrian friendly streetscapes.

- Price on-street parking in residential neighborhoods. Create Parking Benefit Districts, with revenues used to benefit local communities (Shoup, 1995).

- Allow motorists to lease on-street parking spaces (Solomon, 1995). For example, let residents and businesses lease the parking spaces in front of their homes or shops, which they could use themselves, reserve for their visitors and customers, or rent to other motorists.

- Use TDM Marketing and other information resources to provide information on parking prices and availability, and on alternative travel options.

- Develop and utilize Transportation Management Associations to provide parking management, user information and brokerage services in a particular area.

- Use parking pricing revenues to Fund Transportation Programs.

- Provide free or discounted parking to Rideshare vehicles

Parking Management Benefits

In Parking Management: Comprehensive Implementation Guide, Todd Litman lists the following benefits of Parking Management:

- Facility cost savings. Reduces costs to governments, businesses, developers and consumers

- Improved quality of service. Many strategies improve user quality of service by providing better information, increasing consumer options, reducing congestion and creating more attractive facilities

- More flexible facility location and design. Parking management gives architects, designers and planners more ways to address parking requirements

- Revenue generation. Some management strategies generate revenues that can fund parking facilities, transportation improvements, or other important projects

- Reduces land consumption. Parking management can reduce land requirements to help to preserve greenspace and other valuable ecological, historic and cultural resources

- Supports mobility management. Parking management is an important component of efforts to encourage more efficient transportation patterns, which helps reduce problems such as traffic congestion, roadway costs, pollution emissions, energy consumption and traffic accidents

- Supports Smart Growth. Parking management helps create more accessible and efficient land use patterns, and support other land use planning objectives

- Improved walkability. By allowing more clustered development and buildings located closer to sidewalks and streets, parking management helps create more walkable communities

- Supports transit. Parking management supports transit-oriented development and transit use

- Reduced stormwater management costs, water pollution and heat island effects. Parking management can reduce total pavement area and incorporate design features such as landscaping and shading that reduce stormwater flow, water pollution and solar heat gain

- Supports equity objectives. Management strategies can reduce the need for parking subsidies, improve travel options for non-drivers, provide financial savings to lower-income households, and increase housing affordability

- More livable communities. Parking management can help create more attractive and efficient urban environments by reducing total paved areas, allowing more flexible building design, increasing walkability and improving parking facility design

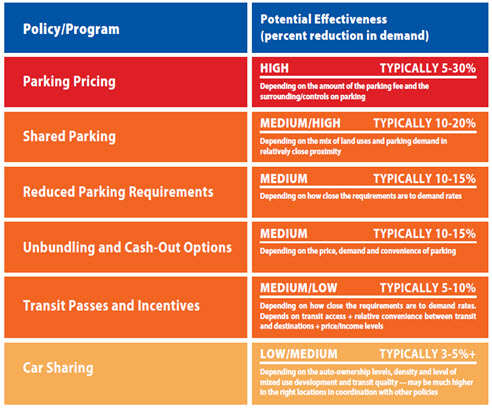

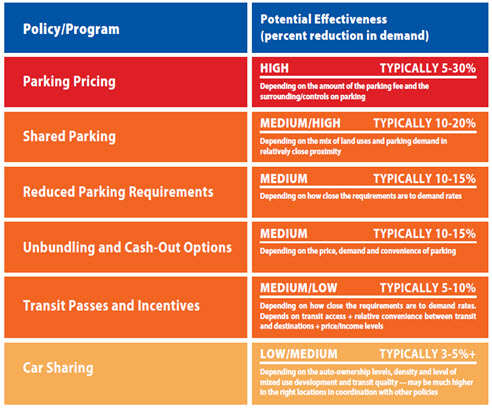

Effectiveness of Parking Policies to Reduce Parking Demand

San Francisco's Metropolitan Transportation Commission prepared a document called Parking Policies to Support Smart Growth: http://www.mtc.ca.gov/planning/smart_growth/parking_policies_flyer-web.pdf. They evaluated various strategies and their effectiveness at reducing parking demand:

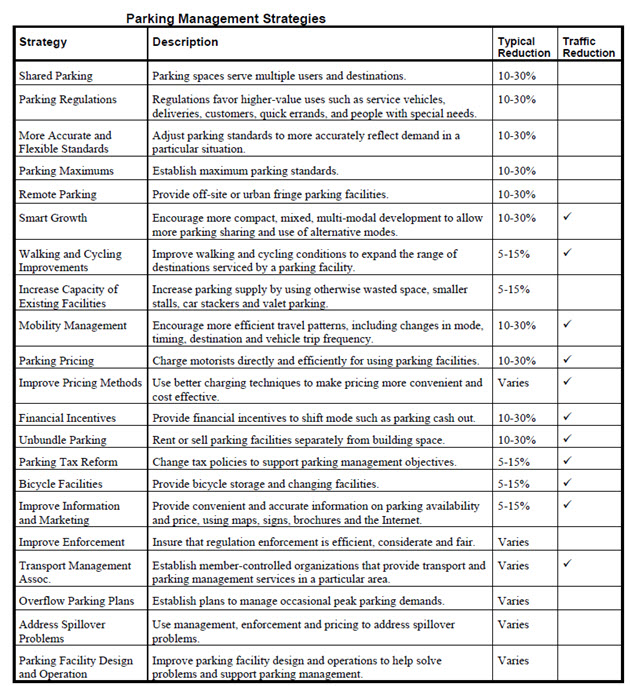

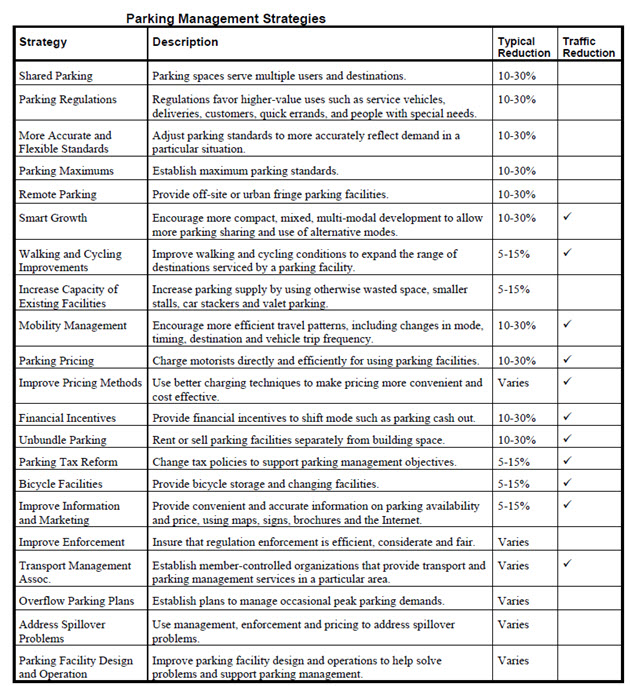

Todd Litman has compiled a similar analysis:

(Litman, 2006)

Factors Affecting Cost of Parking Structure

All information in this section is taken directly from International Parking Design (IPD) firm's website:

http://www.ipd-global.com/whats_it_cost/

Above-Grade

How much do parking structures cost? This is one of the first questions clients ask. Before we can respond, we need to know the answers to the following questions:

- How many spaces do you need?

- How many levels?

- What size is the site?

The answers have a major impact on the cost-per-space figure for a particular parking structure. Cost per space is dependent on two factors: Area per Space and Cost per Square Foot.

Area per Space

The area per space is affected by several factors, including the type of user, size of the site, shape of site, city parking requirements, and the type of flow system.

Type of User: Retail customer parking requires more generous parking dimensions than office employee parking, hence a higher area per space.

Size of Site: A narrow site may dictate a shallow angle of parking that results in a higher area per space than steeper angles or ninety-degree parking. A shorter site may require a speed ramp rather than a parking ramp, resulting in higher area per space.

Shape of Site: Irregular shapes create wasted areas within the parking structure.

Muncipal Parking Requirements: Some cities require wider spaces and aisles than others, no matter who the user is, resulting in a higher area per space.

Type of Flow: A level-floor structure with connecting express ramps will result in a higher area per space than one with sloping parking ramps.

Cost per Square Foot

To calculate the cost per square foot, the following considerations must be weighed.

- Geographical Location: Costs vary considerably by geographic region.

- Number of Levels: Taller structures have a higher average cost per square foot because elevated levels are more costly than the ground level.

- Shape of Site: The length of exterior facade per square foot of area is greater on small sites than on larger sites and greater on long, narrow sites than on square sites, resulting in higher costs.

- Topography: Sloping sites usually result in expensive retaining walls.

- Soil Conditions: Poor soil conditions result in higher foundation costs.

- Exterior Architectural Treatment: High-level architectural treatments can increase costs significantly.

Underground Parking Structures

Estimating costs for underground parking structures is considerably more complicated than costs for above-grade structures. Factors that contribute to the complexity include:

- The extent of shoring, if any, which will be required;

- Whether or not the parking is located below another use, which may dictate whether the structural system will be short-span or long-span;

- Location of water table in relation to the lowest level; and

- Whether or not the "lid" or plaza level over the parking is to be included in the cost of parking.

Shoring

The amount of wall to be shored depends primarily on the site. In some cases, the exterior walls may be far enough from property lines that slope cutting can be used on all sides instead of shoring. In other cases, all walls may be adjacent to property lines and require shoring. Any number of possibilities exists between these extremes. The unit cost of shoring depends on soil conditions and depth of excavation.

Other Uses above Parking

If the underground parking is part of a freestanding parking structure with no other uses above, the same long-span structural system can be carried below grade and there is no penalty in parking layout efficiency.

If office, retail, residential, or hotel uses are above the below-grade parking, the structural system of the use above is carried down through the parking levels and parking layout efficiency may be severely impacted. For example, if the columns are spaced 32'-0" apart and code-required space width is 8'-6", only 3 spaces can be placed between columns, resulting in a 25% penalty, compared to a layout with a long-span structural system.

If parking is placed below a plaza or park with heavy landscape loads, a short-span structural system may be necessary, but in this case, the parking layout can dictate the location of columns rather than the building above, and the penalty in efficiency compared to that of a long-span structure is closer to 15%.

Other efficiency penalties that occur when another use is placed above parking include losses for elevators, mechanical rooms or electrical rooms that serve the use above and are located in the parking facility.

Water Table Location

If the water table is above the bottom of foundations, additional costs will be incurred for dewatering during construction. Cost of dewatering is a function of the depth below the water table, the area to be dewatered and the length of time dewatering will be required.

If the structure gets deep enough into water, the walls and grade slab must be designed for hydrostatic pressures, and, in some cases, additional structure weight must be provided to prevent "floating." These measures can add significantly to structure cost.

Allocation of Cost of Plaza Level

When another use is built above the parking structure, there is a grade-level or plaza-level structural cost that must be allocated either to the parking or to the building above. This is a cost that would not occur if the two uses were built side-by-side and the top parking level was open to the sky. The office, hotel or retail building would only have the cost of a grade slab included, which is much less than the plaza-level elevated slab supporting landscape loads or other elements.

The cost of the grade-level slab will also be higher than the cost of a typical parking level because it is normally supporting added dead loads such as paving or landscaping, plus higher live loads than parking requires. The costs of paving or landscaping would be in addition to the structural cost.

Calculation of Cost per Space

Normally, the cost per space can be approximated by multiplying area per space by the average cost per square foot. In the case of underground facilities, the cost of the grade-level deck, which provides no parking spaces, must also be taken into consideration. The cost per square foot of the lowest level is calculated by including the slab-on-grade, foundations, exterior walls, ventilation, fire sprinklers, excavation and shoring costs, in addition to the normal lighting, signing, painting, stairs, elevators, etc. that are appropriate for that level.

The cost of the typical parking level would be calculated in a similar manner, using the cost of the elevated beam-and-slab system in lieu of the slab-on-grade.

The cost of the grade-level, or plaza level, slab is calculated using only the structural cost of the beam-and-slab system and any improvements above it that are appropriate.

The area per space, as mentioned above, will depend on whether column spacing is dictated by another use above, or whether a long-span structural system can be employed. Area per space is also dependent on standards for space size and aisle width dictated by local planning codes.

Other Resources

Transportation Authority of Marin's Parking Guidance Guide: http://www.tam.ca.gov/index.aspx?page=271

Toronto's Design Guidelines for ‘Greening' Surface Parking Lots:

http://www.toronto.ca/planning/urbdesign/greening_parking_lots.htm

MTC's Developing Parking Policies to Support Smart Growth in Local Jurisdictions: Best Practices:

http://www.mtc.ca.gov/planning/smart_growth/parking_seminar/BestPractices.pdf

Litman's Parking Management: Comprehensive Implementation Guide:

http://www.vtpi.org/park_man_comp.pdf

EPA's Parking Spaces / Community Places:

http://www.epa.gov/dced/parking.htm

References

Baron, Philip J. and John W. Dorsett. 2004. "Parking Facility Economics and Approaches to Financing," in Haahs, Timothy H., ed. Parking Management – The Next Level, Parking 101 Vol. 2. Fredericksburg, VA: International Parking Institute.

Bier, Leonard, Gerard Giosa, Robert S. Goldsmith, Richard Johnson, and Darius Sollohub. 2006. Parking Matters: Designing, Operating and Financing Structured Parking in Smart Growth Communities. Airmont, NJ: the Urban Land Institute-Northern New Jersey. Online: http://bit.ly/748MxH

Bloomberg, Michael. 2009. "My big parking promises: Mayor Bloomberg serves up a plan for N.Y.C drivers" in NYDailyNews.com, 9/13/2009. http://bit.ly/5IOACj (Accessed: 10/16/09)

Boston Metropolitan Area Planning Council. Sustainable Transportation Toolkit: Parking, 2007. http://transtoolkit.mapc.org/Parking/Strategies/mitigating_environmental_impacts.htm (Accessed: 09/09/09)

Burns, Dennis L. and Melinda Anderson. 2004. "Developing an Annual Parking Report," in Haahs, Timothy H., ed. Parking Management – The Next Level, Parking 101 Vol. 2. Fredericksburg, VA: International Parking Institute.

Chicago Receives $1.157 Billion Winning Bid for Metered Parking System. December 2008. Press release, City of Chicago. Online:http://bit.ly/76fw53

How to Handle Parking. 2007. Transit-Friendly Development Newsletter 3 (1). http://policy.rutgers.edu/vtc/tod/newsletter/vol3-num1/TODParking.html Accessed 3 August 2009.

Kane County Transit Opportunity Assessment Study. http://www.co.kane.il.us/dot/COM/Transit/01execsum.pdf (Accessed 10/1/09).

Kuzmyak, Richard J., Rachel Weinberger, Richard H. Pratt and Herbert Levinson. 2003. Parking Management and Supply: TCRP Report 95, Chapter 18. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rpt_95c18.pdf

Litman, Todd. 2008. Parking Pricing: Direct Charges for Using Parking Facilities. TDM Encylcopedia, Victoria Transport Policy Institute. http://www.vtpi.org/tdm/tdm26.htm, Accessed: 09/09/09.

Litman, Todd. 2006. Parking Management: Strategies, Evaluation and Planning. Summary of Parking Management Best Practices. Chicago: APA Planners Press. Online: http://www.vtpi.org/park_man.pdf

Manville, Michael and Donald Shoup. 2005. Parking, People and Cities. Journal of Urban Planning and Development 131 (4): 233-245.

Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC). 2007. Developing Parking Policies to Support Smart Growth in Local Jurisdictions: Best Practices. Wilbur Smith Associates: http://www.mtc.ca.gov/planning/smart_growth/parking_seminar/BestPractices.pdf

Naperville Finance Department. Telephone interview, 1 October 2009.

Nicholas, Arthur C. 2004. Non-Central City Expressway Park-n-Ride Lot Preliminary Site Analysis for Northeastern Illinois. Working Paper 04-01, Chicago Area Transportation Study. Available online: http://www.catsmpo.org/workingpapers/04-01.pdf

Northwestern University Newsletter. 2006. Accessed 09/10/09. http://www.northwestern.edu/newscenter/stories/2006/01/parking.html

Regional Transportation Authority (Chicago). 1998. Opportunity Costs of Municipal Parking Requirements, Prepared by Fish & Associates, K.T. Analytics, and Vlecides-Schroeder Associates, Final Report, April.

Roth, Gary. 2004. An Investigation Into Rational Pricing For Curbside Parking: What Will Be The Effects Of Higher Curbside Parking Prices In Manhattan? Masters Thesis, Columbia University; http://bit.ly/8bHM8M.

Shoup, Donald. 2005. The High Cost of Free Parking. Chicago: APA Planners Press.

Shoup, Donald. 2003. "The High Cost of Free Parking." Presentation to the International Symposium on Road Pricing. November. www.trb.org/Conferences/RoadPricing/Presentations/Shoup.ppt

Smith, Mary. 2005. Shared Parking, Second Edition. Washington, D.C.: ULI-the Urban Land Institute and the International Council of Shopping Centers. Transportation Authority of Marin, TPLUS TOD/PeD Toolkit. Accessed 09/09/09. http://www.tam.ca.gov/index.aspx?page=293

Turnbull, Katherine F., et al. 2004. Park-and-Ride/Pool: TCRP Report 95, Chapter 3. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board, 2004. http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rpt_95c3.pdf

USEPA - Office of Air and Radiation. 2005. Parking Cash Out: Implementing Commuter Benefits as One of the Nation's Best Workplaces for CommutersSM. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Village of Northbrook Memorandum. http://bit.ly/80mZ8n.

Weant, Robert A. and Herbert S. Levinson. 1990. Parking. Washington, DC: ENO Transportation Foundation.

Wilson, Richard and Donald C. Shoup. "Parking Subsidies and Travel Choices: Assessing the Evidence." Transportation, 17: 141-157. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands: 1990.

Sep 15, 2013

Appendix

This appendix provides information that can be useful to municipalities that are interested in evaluating parking strategies and creating new policies.

Parking Pricing Techniques

Todd Litman's Parking Pricing techniques offer a succinct version of many strategies presented in this paper (2008):

- Wherever possible, charge motorists directly for using parking facilities. If parking must be subsidized, offer comparable benefits for use of other travel modes, such as Cash Out payments.

- Manage and price the most convenient parking spaces to favor priority users. Charge higher rates and use shorter pricing periods at more convenient parking spaces (such as on-street spaces, and parking near building entrances) to increase turnover and favor higher-priority uses. Prime spaces suitable for short-term use should generally be at least twice as expensive per unit of time as less-convenient spaces suitable for longer-term uses. For example, in a central business district charge 25¢ for each 15-minute period with a two-hour limit, while at the fringe charge $4 per day. The ratio between short- and long-term spaces may need occasional adjustment to optimize use.

- Use variable rates that are higher for peak locations and times. Apply performance-based parking prices, which means that prices are set so that about 15% of parking spaces are unoccupied during peak periods (Shoup, 2006). For example, charge $1 per hour for parking downtown during weekdays, $0.75 per hour for parking downtown during evenings and weekends, and $0.50 per hour for parking in other locations.

- Improve Pricing Methods to make Parking Pricing more cost effective, convenient and fair. For example, use electronic pricing systems that accommodate various payment methods and rates, and allow motorists to pay for just the amount of time they will be parked. For short-term parking charge by the minute rather than by the hour, and for long-term parking charge by the hour rather than by the day or month.

- Avoid discounts for long-term parking leases (i.e., cheap monthly rates).

- Use a progressive price structure in more convenient spaces to favor short-term users. For example, charge $1.00 for the first hour, $1.50 for the second hour, and $2 for each subsequent hour.

- To increase revenues, expand when and where parking is priced rather than raising rates at existing priced facilities. This is more efficient and equitable, reduces spillover problems, and usually raises more total revenue.

- Set parking prices to equal or exceed transit fares. For example, set daily rates at least equal to two single transit fares, and monthly rates at least equal to a monthly transit pass.

- Minimize discounts for long-term parking passes. For example, set daily rates at least 6 times the hourly rates, and monthly rates at least 20 times daily rates. Even better, eliminate unlimited-use passes altogether. Instead, sell books of daily tickets, so commuters save money every day they avoid driving.

- Eliminate early-bird discounts.

- Unbundle parking, so people who rent or purchase building space can choose how much parking is included.

- Avoid excessive parking supply. Use Parking Management to encourage more efficient use of existing parking facilities and address any spillover problems that result from pricing.

- Encourage businesses to price, cash out and unbundle parking by providing rewards to those that do, legislating it, or by imposing special property taxes on un-priced parking.

- Unbundle parking from housing, so apartment and condominium residents pay only for the parking spaces they need (Location Efficient Development).

- If parking must be subsidized, use targeted discounts and exemptions, rather than offering free parking to everybody. For example, to subsidize customer parking, allow businesses to validate parking tickets or provide free parking coupons to customers. To subsidize parking for people with low incomes or disabilities, provide discounts directly to those individuals.

- Tax parking spaces, and encourage or require that this cost be passed on to users. Reform existing tax policies that favor free parking. For example, tax land devoted to parking at the same rate as land used for other development.

- Charge a tax on curbcuts comparable to potential revenue foregone had the same curb area been devoted to priced on-street parking. This would encourage property owners to minimize the number and width of curb cuts, through access management and consolidation of driveways and parking facilities, which helps improve traffic flow and create more pedestrian friendly streetscapes.

- Price on-street parking in residential neighborhoods. Create Parking Benefit Districts, with revenues used to benefit local communities (Shoup, 1995).

- Allow motorists to lease on-street parking spaces (Solomon, 1995). For example, let residents and businesses lease the parking spaces in front of their homes or shops, which they could use themselves, reserve for their visitors and customers, or rent to other motorists.

- Use TDM Marketing and other information resources to provide information on parking prices and availability, and on alternative travel options.

- Develop and utilize Transportation Management Associations to provide parking management, user information and brokerage services in a particular area.

- Use parking pricing revenues to Fund Transportation Programs.

- Provide free or discounted parking to Rideshare vehicles

Parking Management Benefits

In Parking Management: Comprehensive Implementation Guide, Todd Litman lists the following benefits of Parking Management:

- Facility cost savings. Reduces costs to governments, businesses, developers and consumers

- Improved quality of service. Many strategies improve user quality of service by providing better information, increasing consumer options, reducing congestion and creating more attractive facilities

- More flexible facility location and design. Parking management gives architects, designers and planners more ways to address parking requirements

- Revenue generation. Some management strategies generate revenues that can fund parking facilities, transportation improvements, or other important projects

- Reduces land consumption. Parking management can reduce land requirements to help to preserve greenspace and other valuable ecological, historic and cultural resources

- Supports mobility management. Parking management is an important component of efforts to encourage more efficient transportation patterns, which helps reduce problems such as traffic congestion, roadway costs, pollution emissions, energy consumption and traffic accidents

- Supports Smart Growth. Parking management helps create more accessible and efficient land use patterns, and support other land use planning objectives

- Improved walkability. By allowing more clustered development and buildings located closer to sidewalks and streets, parking management helps create more walkable communities

- Supports transit. Parking management supports transit-oriented development and transit use

- Reduced stormwater management costs, water pollution and heat island effects. Parking management can reduce total pavement area and incorporate design features such as landscaping and shading that reduce stormwater flow, water pollution and solar heat gain

- Supports equity objectives. Management strategies can reduce the need for parking subsidies, improve travel options for non-drivers, provide financial savings to lower-income households, and increase housing affordability

- More livable communities. Parking management can help create more attractive and efficient urban environments by reducing total paved areas, allowing more flexible building design, increasing walkability and improving parking facility design

Effectiveness of Parking Policies to Reduce Parking Demand

San Francisco's Metropolitan Transportation Commission prepared a document called Parking Policies to Support Smart Growth: http://www.mtc.ca.gov/planning/smart_growth/parking_policies_flyer-web.pdf. They evaluated various strategies and their effectiveness at reducing parking demand:

Todd Litman has compiled a similar analysis:

(Litman, 2006)

Factors Affecting Cost of Parking Structure

All information in this section is taken directly from International Parking Design (IPD) firm's website:

http://www.ipd-global.com/whats_it_cost/

Above-Grade

How much do parking structures cost? This is one of the first questions clients ask. Before we can respond, we need to know the answers to the following questions:

- How many spaces do you need?

- How many levels?

- What size is the site?

The answers have a major impact on the cost-per-space figure for a particular parking structure. Cost per space is dependent on two factors: Area per Space and Cost per Square Foot.

Area per Space

The area per space is affected by several factors, including the type of user, size of the site, shape of site, city parking requirements, and the type of flow system.

Type of User: Retail customer parking requires more generous parking dimensions than office employee parking, hence a higher area per space.

Size of Site: A narrow site may dictate a shallow angle of parking that results in a higher area per space than steeper angles or ninety-degree parking. A shorter site may require a speed ramp rather than a parking ramp, resulting in higher area per space.

Shape of Site: Irregular shapes create wasted areas within the parking structure.

Muncipal Parking Requirements: Some cities require wider spaces and aisles than others, no matter who the user is, resulting in a higher area per space.

Type of Flow: A level-floor structure with connecting express ramps will result in a higher area per space than one with sloping parking ramps.

Cost per Square Foot

To calculate the cost per square foot, the following considerations must be weighed.

- Geographical Location: Costs vary considerably by geographic region.

- Number of Levels: Taller structures have a higher average cost per square foot because elevated levels are more costly than the ground level.

- Shape of Site: The length of exterior facade per square foot of area is greater on small sites than on larger sites and greater on long, narrow sites than on square sites, resulting in higher costs.

- Topography: Sloping sites usually result in expensive retaining walls.

- Soil Conditions: Poor soil conditions result in higher foundation costs.

- Exterior Architectural Treatment: High-level architectural treatments can increase costs significantly.

Underground Parking Structures

Estimating costs for underground parking structures is considerably more complicated than costs for above-grade structures. Factors that contribute to the complexity include:

- The extent of shoring, if any, which will be required;

- Whether or not the parking is located below another use, which may dictate whether the structural system will be short-span or long-span;

- Location of water table in relation to the lowest level; and

- Whether or not the "lid" or plaza level over the parking is to be included in the cost of parking.

Shoring

The amount of wall to be shored depends primarily on the site. In some cases, the exterior walls may be far enough from property lines that slope cutting can be used on all sides instead of shoring. In other cases, all walls may be adjacent to property lines and require shoring. Any number of possibilities exists between these extremes. The unit cost of shoring depends on soil conditions and depth of excavation.

Other Uses above Parking

If the underground parking is part of a freestanding parking structure with no other uses above, the same long-span structural system can be carried below grade and there is no penalty in parking layout efficiency.

If office, retail, residential, or hotel uses are above the below-grade parking, the structural system of the use above is carried down through the parking levels and parking layout efficiency may be severely impacted. For example, if the columns are spaced 32'-0" apart and code-required space width is 8'-6", only 3 spaces can be placed between columns, resulting in a 25% penalty, compared to a layout with a long-span structural system.

If parking is placed below a plaza or park with heavy landscape loads, a short-span structural system may be necessary, but in this case, the parking layout can dictate the location of columns rather than the building above, and the penalty in efficiency compared to that of a long-span structure is closer to 15%.

Other efficiency penalties that occur when another use is placed above parking include losses for elevators, mechanical rooms or electrical rooms that serve the use above and are located in the parking facility.

Water Table Location

If the water table is above the bottom of foundations, additional costs will be incurred for dewatering during construction. Cost of dewatering is a function of the depth below the water table, the area to be dewatered and the length of time dewatering will be required.

If the structure gets deep enough into water, the walls and grade slab must be designed for hydrostatic pressures, and, in some cases, additional structure weight must be provided to prevent "floating." These measures can add significantly to structure cost.

Allocation of Cost of Plaza Level

When another use is built above the parking structure, there is a grade-level or plaza-level structural cost that must be allocated either to the parking or to the building above. This is a cost that would not occur if the two uses were built side-by-side and the top parking level was open to the sky. The office, hotel or retail building would only have the cost of a grade slab included, which is much less than the plaza-level elevated slab supporting landscape loads or other elements.

The cost of the grade-level slab will also be higher than the cost of a typical parking level because it is normally supporting added dead loads such as paving or landscaping, plus higher live loads than parking requires. The costs of paving or landscaping would be in addition to the structural cost.

Calculation of Cost per Space

Normally, the cost per space can be approximated by multiplying area per space by the average cost per square foot. In the case of underground facilities, the cost of the grade-level deck, which provides no parking spaces, must also be taken into consideration. The cost per square foot of the lowest level is calculated by including the slab-on-grade, foundations, exterior walls, ventilation, fire sprinklers, excavation and shoring costs, in addition to the normal lighting, signing, painting, stairs, elevators, etc. that are appropriate for that level.

The cost of the typical parking level would be calculated in a similar manner, using the cost of the elevated beam-and-slab system in lieu of the slab-on-grade.

The cost of the grade-level, or plaza level, slab is calculated using only the structural cost of the beam-and-slab system and any improvements above it that are appropriate.

The area per space, as mentioned above, will depend on whether column spacing is dictated by another use above, or whether a long-span structural system can be employed. Area per space is also dependent on standards for space size and aisle width dictated by local planning codes.

Other Resources

Transportation Authority of Marin's Parking Guidance Guide: http://www.tam.ca.gov/index.aspx?page=271

Toronto's Design Guidelines for ‘Greening' Surface Parking Lots:

http://www.toronto.ca/planning/urbdesign/greening_parking_lots.htm

MTC's Developing Parking Policies to Support Smart Growth in Local Jurisdictions: Best Practices:

http://www.mtc.ca.gov/planning/smart_growth/parking_seminar/BestPractices.pdf

Litman's Parking Management: Comprehensive Implementation Guide:

http://www.vtpi.org/park_man_comp.pdf

EPA's Parking Spaces / Community Places:

http://www.epa.gov/dced/parking.htm

References

Baron, Philip J. and John W. Dorsett. 2004. "Parking Facility Economics and Approaches to Financing," in Haahs, Timothy H., ed. Parking Management – The Next Level, Parking 101 Vol. 2. Fredericksburg, VA: International Parking Institute.

Bier, Leonard, Gerard Giosa, Robert S. Goldsmith, Richard Johnson, and Darius Sollohub. 2006. Parking Matters: Designing, Operating and Financing Structured Parking in Smart Growth Communities. Airmont, NJ: the Urban Land Institute-Northern New Jersey. Online: http://bit.ly/748MxH

Bloomberg, Michael. 2009. "My big parking promises: Mayor Bloomberg serves up a plan for N.Y.C drivers" in NYDailyNews.com, 9/13/2009. http://bit.ly/5IOACj (Accessed: 10/16/09)

Boston Metropolitan Area Planning Council. Sustainable Transportation Toolkit: Parking, 2007. http://transtoolkit.mapc.org/Parking/Strategies/mitigating_environmental_impacts.htm (Accessed: 09/09/09)

Burns, Dennis L. and Melinda Anderson. 2004. "Developing an Annual Parking Report," in Haahs, Timothy H., ed. Parking Management – The Next Level, Parking 101 Vol. 2. Fredericksburg, VA: International Parking Institute.

Chicago Receives $1.157 Billion Winning Bid for Metered Parking System. December 2008. Press release, City of Chicago. Online:http://bit.ly/76fw53

How to Handle Parking. 2007. Transit-Friendly Development Newsletter 3 (1). http://policy.rutgers.edu/vtc/tod/newsletter/vol3-num1/TODParking.html Accessed 3 August 2009.

Kane County Transit Opportunity Assessment Study. http://www.co.kane.il.us/dot/COM/Transit/01execsum.pdf (Accessed 10/1/09).

Kuzmyak, Richard J., Rachel Weinberger, Richard H. Pratt and Herbert Levinson. 2003. Parking Management and Supply: TCRP Report 95, Chapter 18. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rpt_95c18.pdf

Litman, Todd. 2008. Parking Pricing: Direct Charges for Using Parking Facilities. TDM Encylcopedia, Victoria Transport Policy Institute. http://www.vtpi.org/tdm/tdm26.htm, Accessed: 09/09/09.

Litman, Todd. 2006. Parking Management: Strategies, Evaluation and Planning. Summary of Parking Management Best Practices. Chicago: APA Planners Press. Online: http://www.vtpi.org/park_man.pdf

Manville, Michael and Donald Shoup. 2005. Parking, People and Cities. Journal of Urban Planning and Development 131 (4): 233-245.

Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC). 2007. Developing Parking Policies to Support Smart Growth in Local Jurisdictions: Best Practices. Wilbur Smith Associates: http://www.mtc.ca.gov/planning/smart_growth/parking_seminar/BestPractices.pdf

Naperville Finance Department. Telephone interview, 1 October 2009.

Nicholas, Arthur C. 2004. Non-Central City Expressway Park-n-Ride Lot Preliminary Site Analysis for Northeastern Illinois. Working Paper 04-01, Chicago Area Transportation Study. Available online: http://www.catsmpo.org/workingpapers/04-01.pdf

Northwestern University Newsletter. 2006. Accessed 09/10/09. http://www.northwestern.edu/newscenter/stories/2006/01/parking.html

Regional Transportation Authority (Chicago). 1998. Opportunity Costs of Municipal Parking Requirements, Prepared by Fish & Associates, K.T. Analytics, and Vlecides-Schroeder Associates, Final Report, April.

Roth, Gary. 2004. An Investigation Into Rational Pricing For Curbside Parking: What Will Be The Effects Of Higher Curbside Parking Prices In Manhattan? Masters Thesis, Columbia University; http://bit.ly/8bHM8M.

Shoup, Donald. 2005. The High Cost of Free Parking. Chicago: APA Planners Press.

Shoup, Donald. 2003. "The High Cost of Free Parking." Presentation to the International Symposium on Road Pricing. November. www.trb.org/Conferences/RoadPricing/Presentations/Shoup.ppt

Smith, Mary. 2005. Shared Parking, Second Edition. Washington, D.C.: ULI-the Urban Land Institute and the International Council of Shopping Centers. Transportation Authority of Marin, TPLUS TOD/PeD Toolkit. Accessed 09/09/09. http://www.tam.ca.gov/index.aspx?page=293

Turnbull, Katherine F., et al. 2004. Park-and-Ride/Pool: TCRP Report 95, Chapter 3. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board, 2004. http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rpt_95c3.pdf

USEPA - Office of Air and Radiation. 2005. Parking Cash Out: Implementing Commuter Benefits as One of the Nation's Best Workplaces for CommutersSM. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Village of Northbrook Memorandum. http://bit.ly/80mZ8n.

Weant, Robert A. and Herbert S. Levinson. 1990. Parking. Washington, DC: ENO Transportation Foundation.

Wilson, Richard and Donald C. Shoup. "Parking Subsidies and Travel Choices: Assessing the Evidence." Transportation, 17: 141-157. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands: 1990.