Providing a generous parking supply is costly, ranging from about $250 to $2,250 per space (direct, annualized cost calculated by Litman 2006). These costs, however, do not include the indirect costs that municipalities face, such as: "increased sprawl, impervious surface and associated stormwater management costs, reduced design flexibility, reduced efficiency of alternative modes (walking, ridesharing and public transit use), and increased traffic problems" (Ibid). In this section, we will examine how parking management can affect these different areas.

Our development patterns have created a landscape that is often dominated by the car. Since a car spends 95% of its life parked (Shoup 2005), much of the landscape has been turned into parking lots. In many cases, residents of auto-oriented communities would like to have more transportation options, but the low-density associated with a generous parking supply makes this unfeasible. Also, residents who are opposed to new developments with increased density often cite fears of increased traffic and parking difficulties. Unfortunately, the reality is that low-density development patterns preclude transit options and force more people to drive.

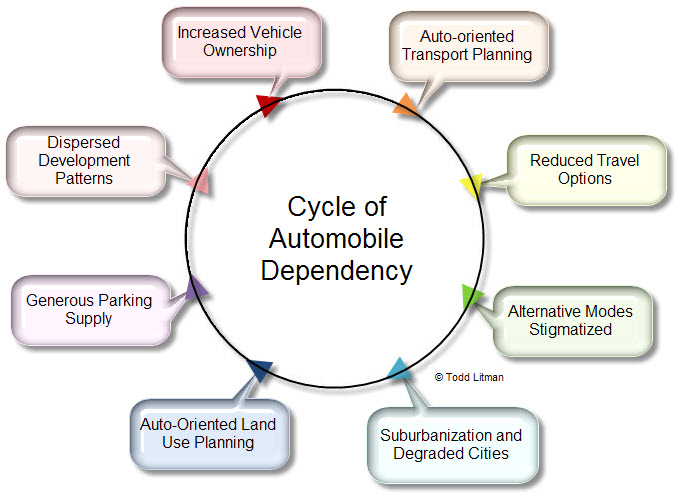

Todd Litman's "Cycle of Automobile Dependency" shows how auto-centric land use planning and excessive parking supply have created this situation. Parking management strategies can be used to break this cycle, by changing development patterns and improving travel options (2006).

Todd Litman's "Cycle of Automobile Dependency" shows how auto-centric land use planning and excessive parking supply have created this situation. Parking management strategies can be used to break this cycle, by changing development patterns and improving travel options (2006).

The impacts of parking management strategies will vary depending on a number of factors, and they will be higher when travelers have alternative transportation options. But even in the absence of transit, it is still possible to use parking strategies to affect land use, congestion, and environmental degradation.