Parking management embraces a variety of strategies that seek to either reduce parking spaces needed or to use parking spaces more efficiently. Parking management arose out of a concern that parking lots and off-street parking cover a significant proportion of urban areas, particularly high-demand regions such as central business districts. The Chicago CBD is thought to have over 975 acres of parking (Manville and Shoup, 2005). This coverage is viewed by some as an urban eyesore, reducing walkability, and depriving the city of additional property tax revenues (parking lots are often in high-demand areas where land has a high value). Parking management proponents argue that these vast amounts of high-value land could be put to better use.

Given the unique qualities of individual communities, it is difficult to say what the minimum or maximum parking requirements in our region should be, even if specified by land use. Litman considers ‘optimal parking supply' to be "the amount that motorists would purchase if they paid all costs directly and had good parking and transport options" (2006). Many surveys measuring demand assume that parking is free and do not consider whether an area has alternative modes of transportation. Also, most people are unaware of problems that stem from excessive parking supply. Contemporary parking planners suggest shifting to efficiency-based standards that allow parking lots to become full, using management strategies to take care of overflow and address any potential problems (Litman, 2006 and Shoup, 2007).

Parking management strategies can also promote efficient use of existing parking, such as shared parking plans and improved information on the availability of parking. Parking management techniques are utilized in reforming city ordinances to reduce parking requirements for new development, which are typically designed to accommodate rare peak demand (occurring perhaps once a year) in an auto-only environment. Most parking management projects utilize a variety of strategies, employing each as needed to best address each unique situation. As mentioned in the introduction, it is important for the parking strategies to be flexible, so that they can be easily adjusted to the changing needs of a community.

Maximum and Minimum Requirements

Traditional parking requirements specify a minimum number of spaces to be provided for each land use. Alternatively, planners can use parking maximums to better utilize the space. Parking maximums can be used in addition to, or instead of, parking minimums.

The parking minimums set by most communities are often based on the idea that more parking is better. Too little parking can lead to spill over into neighborhoods and cars circulating unnecessarily looking for parking; most local governments and developers want to avoid such outcomes. Unfortunately, the data used to set minimum parking requirements is often limited and irrelevant. To conduct a full parking study of actual parking needs in a community is usually cost—and time—prohibitive. As a result, most cities either copy the parking codes of other cities or use the Institute of Transportation Engineers' Parking Generation handbook. Even in ITE's handbook, reported parking rates are not necessarily based on much data and the studies feeding into them may come from such varying situations as to have no relevance for the cities consulting the data (Shoup 2005). The existence of transit and/or provision of biking and walking infrastructure can greatly reduce parking needs, and the ITE handbook does not consider such variation between communities.

A 1998 study done for the RTA illustrates this gap between actual demand and supply. A survey of 6 suburban office buildings found that the average parking supply was 3.62 spaces/1,000 square feet (of office building), while the actual demand was 2.45 spaces/1,000 square feet. Building occupancy had a large influence on demand, but even after adjusting the numbers for full occupancy the authors determined that supply could be reduced by 17% and still meet all the existing parking demand. The study recommended that municipalities with more than requirements over 3.5 spaces/1,000 square feet of building revisit their regulations (Regional Transportation Authority 1998). In a nationwide study by Kuzmyak et al., the authors concluded that a parking ratio of 2.0 would sufficiently cover the needs of most business parks, but that each location would have to be analyzed individually to determine special situations or circumstances (2003).

The same study also found that the quantity of parking provided was almost always determined by municipal ordinance or zoning code. In a survey done for the study, most developers reported that they would reduce the amount of parking if they could get a higher return on investment via more development, or if incentives or bonuses were offered. Some developers also worry about the "marketability" of a building if their parking supply is restricted (Kuzmyak et al. 2003). The authors of the RTA study concluded that municipalities would see short-term fiscal benefit only if reduced parking led developers to construct more buildings. In the longer-term, reduced excess parking supply could help to raise land values, which would be to the municipality's benefit (Regional Transportation Authority 1998).

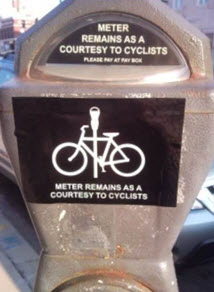

Parking plans should also consider bicycle parking and bicycle facilities as a means to reduce the number of spaces necessary. Many lots will use irregular or small spaces for bicycle and motorcycle parking. When converting from parking meters to pay-box systems, planners should consider the potential bicycle parking that is lost with the removal of meters. Some cities have removed the top of the meter and replaced it with an ornamental decoration, enabling bicyclists to continue using the meter as a bike rack, and reducing costs associated with meter removal and construction of bike racks. In Chicago, where pay boxes have been installed, some meters have a sticker informing people to pay for parking at the box, and that the "meter remains as a courtesy to cyclists." For more on bicycle facilities and planning, see the bicycling strategy paper.

Parking plans should also consider bicycle parking and bicycle facilities as a means to reduce the number of spaces necessary. Many lots will use irregular or small spaces for bicycle and motorcycle parking. When converting from parking meters to pay-box systems, planners should consider the potential bicycle parking that is lost with the removal of meters. Some cities have removed the top of the meter and replaced it with an ornamental decoration, enabling bicyclists to continue using the meter as a bike rack, and reducing costs associated with meter removal and construction of bike racks. In Chicago, where pay boxes have been installed, some meters have a sticker informing people to pay for parking at the box, and that the "meter remains as a courtesy to cyclists." For more on bicycle facilities and planning, see the bicycling strategy paper.