A school's proximity to existing infrastructure, the accessibility of the school by multiple modes of transportation, parking, and proximity to other destinations, etc. all influence traffic patterns and usability of the school. School siting has become such an important issue that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has partnered with CEFPI and developed guidelines and best practices for locating schools, primarily using smart growth principles (CEFPI, EPA). In addition, the EPA encourages schools to be developed as community centers and they generally support building schools on small sites. In fact, they even suggest making multiple-story schools to reduce impact on the land:

A school's proximity to existing infrastructure, the accessibility of the school by multiple modes of transportation, parking, and proximity to other destinations, etc. all influence traffic patterns and usability of the school. School siting has become such an important issue that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has partnered with CEFPI and developed guidelines and best practices for locating schools, primarily using smart growth principles (CEFPI, EPA). In addition, the EPA encourages schools to be developed as community centers and they generally support building schools on small sites. In fact, they even suggest making multiple-story schools to reduce impact on the land:

"A centrally located school that is easy for students and citizens to walk or bike to can reduce land needed for parking, bus drop-off and circular traffic. Schools can even use the money they save by using a smaller site to build a multistory school, reducing yet again the needed land and associated costs."(U.S. DOT)

Locating schools close to where people live can reduce the number and length of automobile or bus trips which can lead to a reduction in emissions and an improvement in air quality. The EPA concludes that,

"Schools built close to students, in walkable neighborhoods, can be called neighborhood schools. …. neighborhood schools would reduce traffic, produce a 13 % increase in walking and biking and a reduction of at least 15% in emissions of concern."

When schools are located outside of neighborhoods or central areas, they can become educational islands. This is more likely to occur with high schools than with elementary, middle schools, or junior high schools. When a high school is located away from the bulk of the population of a community, it is less likely that the school will function as a community center. Instead, the school will be viewed as strictly an educational facility. Underutilization of schools can contribute to increased air pollution as trips to this facility generally are longer in length and are made using automobiles. Trip chaining, such as combining multiple errands into one trip, can be negatively impacted if a school is not near other destinations and doesn't lend itself to non-automobile modes of travel.

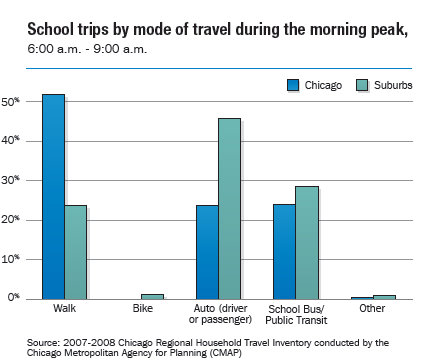

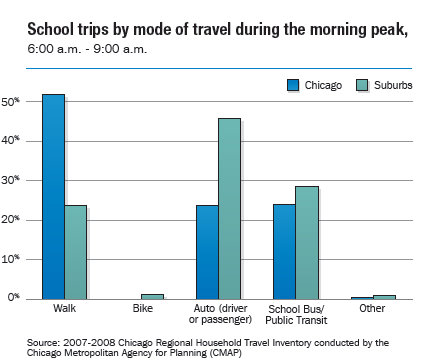

One of the most frequently heard complaints by school administrators has to do with traffic congestion in and around schools during pickup and drop off times. Parents driving kids to school has risen from 15% of all school trips to about 50% from 1969 to 2001 (U.S. DOT). Data from the recently completed Chicago Regional Household Travel Inventory shows that roughly 22% of all the trips in the region during the morning rush period (6-9 am) are school related. Graph 5 (School trips by mode of travel during morning peak) shows the breakdown of school related trips during the morning (6-9 am) by mode, for Chicago and the Suburbs. The results of the Chicago Regional Household Travel Inventory clearly suggest that there are significant differences between city and suburban school trips during the morning rush period. Walking comprised over 50% of city school trips but only slightly more than 23% of suburban school trips, made during the morning commute. In the suburbs driving (either alone or as a passenger) is the dominate mode of transportation, comprising over 45% of morning school trips. It is not surprising then that traffic congestion around suburban schools is frequently cited as a major concern of school officials and police departments throughout the suburbs.

In Illinois, a significant number of children are also bussed to school. In fiscal year 2007, over $325 million dollars were spent to bus students to and from school in Illinois (not including special education). School districts are reimbursed for about 80% of the cost associated with busing if one of 2 conditions is met: the student lives more than 1.5 miles from the school or the route they would have to travel is deemed hazardous.

In Illinois, nearly 84% (795,164) of the students who are bused live more than 1.5 miles from their school, while 16% (153,478) are bused because the route they would travel has been deemed unsafe by the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT). Other than distance, the most common reasons given as to why students do not bike or walk to school are safety related. Concerns about the built environment, traffic, or crime are often given as a justification why students don't walk or bike.

Communities should also consider the costs and benefits associated with renovation versus new construction. The Capital Development board does not differentiate between new buildings, renovations, or additions. As long as overcrowding of students is being addressed, the project will receive a relatively high ranking. Generally speaking, the more over crowed a school is, the higher it is ranked by the CDB. In fact, replacing, renovating, or adding on to an existing school may be cheaper in the long run than building a new school due to reduced land acquisition, infrastructure and transportation cost.

Many of the following recommendations for school siting are derived from case studies and reports, and adapted to fit into the context of northeastern Illinois. Some of the recommendations are planning principles, while others call for a reexamination of how aspects related to selecting a location for a new school or determining the size of a new school are done.

Large campuses can result in high schools that are located in areas that are not bicycle or pedestrian friendly. Schools that are not designed to encourage biking and walking contribute to a myriad of health related issues that are becoming increasingly prevalent in today's school children.

Large campuses can result in high schools that are located in areas that are not bicycle or pedestrian friendly. Schools that are not designed to encourage biking and walking contribute to a myriad of health related issues that are becoming increasingly prevalent in today's school children. A school's proximity to existing infrastructure, the accessibility of the school by multiple modes of transportation, parking, and proximity to other destinations, etc. all influence traffic patterns and usability of the school. School siting has become such an important issue that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has partnered with CEFPI and developed guidelines and best practices for locating schools, primarily using smart growth principles (CEFPI, EPA). In addition, the EPA encourages schools to be developed as community centers and they generally support building schools on small sites. In fact, they even suggest making multiple-story schools to reduce impact on the land:

A school's proximity to existing infrastructure, the accessibility of the school by multiple modes of transportation, parking, and proximity to other destinations, etc. all influence traffic patterns and usability of the school. School siting has become such an important issue that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has partnered with CEFPI and developed guidelines and best practices for locating schools, primarily using smart growth principles (CEFPI, EPA). In addition, the EPA encourages schools to be developed as community centers and they generally support building schools on small sites. In fact, they even suggest making multiple-story schools to reduce impact on the land: