Illinois continues to face a $14 billion (and growing) budget deficit, and following the November elections, new revenue enhancing strategies are being proposed by lawmakers to address both the deficit and education funding. Governor Pat Quinn recently proposed raising the personal income tax by one percentage point as a "surcharge for education" (read more in this November 2010 article from the Chicago Tribune). Given the controversial nature of any tax increase, Quinn seeks to make the proposed tax rate hike more palatable by simultaneously providing "local property tax relief." While an income tax hike could provide billions of dollars in new revenue for the state, "relief" by way of lowering property tax burdens is increasingly complex for a variety of reasons, especially given that local governments, especially Illinois schools, rely heavily on it for revenue. In light of that proposal, this Policy Update will examine some reasons why the income tax and property tax are targeted for reform, some possible implications, and how "property tax relief" might be implemented.

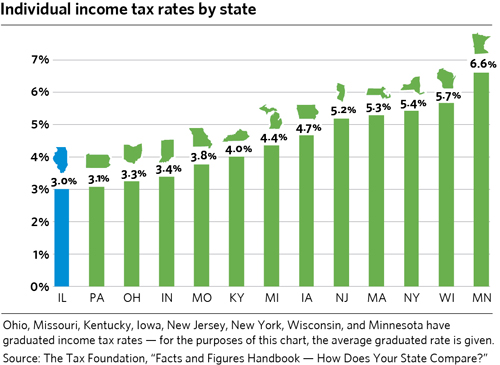

Illinois state income tax rates are among the lowest in the U.S., which could be one of the reasons they were targeted for reform. The Civic Federation's Institute for Illinois' Fiscal Sustainabilitynoted in their 2010 Fiscal Rehabilitation Plan that raising the personal income tax rate from 3 percent to 5 percent and the corporate income tax rate from 4.8 percent to 6.4 percent would provide over $6 billion annually in new revenue to the state.

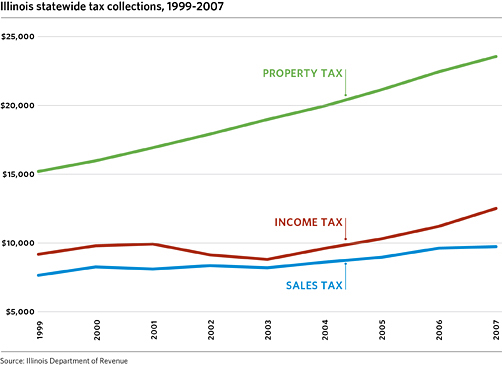

While virtually no tax is widely popular, it is difficult to find one more unpopular than the property tax. In recent years, taxpayers in Illinois paid more in property taxes than state income and sales taxes combined, and revenues from the property tax have grown at a much sharper rate than sales or income taxes have over the past decade. Thus, using property tax relief to sweeten a proposed raise in the personal income tax makes obvious sense.

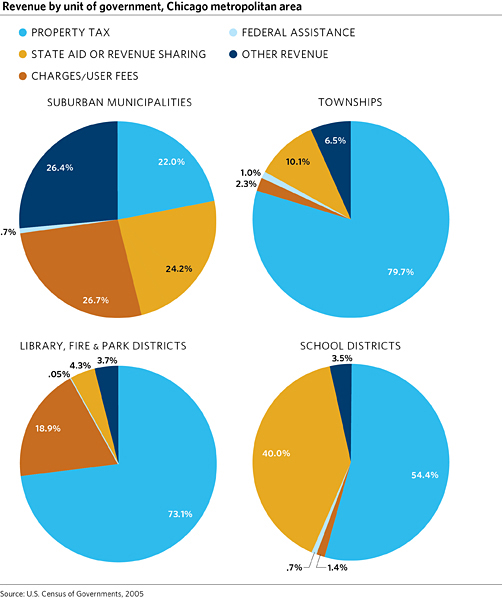

Illinois local governments remain highly reliant on the property tax, relative not only to other states but also to other taxes. Illinois property tax revenues fund local, not state, government services. Moreover, taxpayers typically have a higher level of comfort with highly localized service delivery, which is certainly a tradition in Illinois. Like most other states, local school districts in Illinois are the primary recipients of the property tax. In 2007, schools collected 62 percent of all property tax revenue generated in northeastern Illinois, according to data from the Illinois Department of Revenue. Additionally, schools in Illinois, are also more highly reliant on the property tax than in other states. In fact, Nevada is the only state to rely more on the property tax for school funding than Illinois (read more in this Center for Tax and Budget Accountability [CTBA] Issue Brief on Illinois Property Taxes from 2007).

A true "income/property tax swap" could effectively increase state revenues, which would help to close the budget gap. It could also lower local revenues, especially for schools. However, it is unlikely that such a swap would really be implemented in such a "zero sum" way. Many state revenue sources, including the income tax, are also passed through to local governments in the form of revenue sharing or aid. Counties and municipalities receive roughly one-tenth of income tax collections based on their populations. Furthermore, a share of income tax revenue also flows to funds providing state aid to public schools. Thus, it is quite likely that this debate over the income tax increase may hinge on how this "local flow" of new dollars to counties, municipalities, and schools is implemented. Without a bill in place, it is difficult to predict how an income tax rate increase, partnered with property tax relief, might be operationalized.

The property tax relief side of the swap is also far from clear. The State already caps annual school district property tax extensions in northeastern Illinois through the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law (PTELL). Most other non-home rule taxing districts in northeastern Illinois are also subject to PTELL, which remains in place unless local residents vote it down via referendum. Thus, it is unlikely that the State could add any additional limitations that would actually control local property tax levies themselves (at least not in northeastern Illinois).

However, using past legislation as a guide, "property tax relief" would likely be realized not through more tax caps, but through increasing the amount of property tax revenue that homeowners and businesses can claim on their state income tax bills. Currently, taxpayers can claim up to 5 percent of property taxes paid through this credit. HB 174, which passed the Illinois House in May 2009, would (if signed into law) have increased the personal and corporate income tax rate to 5 percent, as well as expanded the property tax credit to 10 percent. Thus, this form of "property tax relief" is connected more to a taxpayer's income tax bill rather than to the property tax bill itself. HB 174 would have also allocated one third of the increased income tax revenues to the Common School Fund, which would provide more revenues to schools.

Other ideas for reforming Illinois property taxes abound, some of which may have the effect of actually lowering property tax bills themselves. This would likely be viewed more favorably by taxpayers given the unpopularity of the property tax, stemming in part from its high visibility as an annual or semi-annual line item payable to local government units. In a December 2009 report to the Illinois General Assembly, a statewide Property Tax Reform and Relief Task Force recommended a "rebalancing of revenue sources" away from the property tax by connecting property tax relief more closely to the actual property tax bill itself. This would be accomplished by reforming the state's circuit breaker program, which targets relief toward those with lower household incomes. The Task Force recommended running this program with vouchers rather than grants. This differs from the income tax credit system, expanded in HB 174, in that taxpayers could submit these vouchers with property tax payments, thus actually seeing the correlation between the property tax bill and the relief provided.

Of course, another overarching issue in terms of controlling property taxes may be to increase efficiencies at the local government level, primarily by coordinating government services and in some cases, consolidating local governments. Our region ranks first in the U.S. in this measure with over 1,200 units of government.

For many taxing districts, property tax remains the largest source of revenue, composing well over 75 percent of all revenue for townships and other special districts such as fire, park district, and library districts.

Illinois has a long tradition of highly localized governance. The result is an abundance of taxing bodies, along with the rising property tax collections (not to mention state revenue sharing and aid) needed to support them. While increasing state aid to schools through an income tax increase could garner public and political support, many taxpayers also prefer the responsiveness and accountability that local taxes (and thus local control) often promise to deliver. Without question, any suggestion of property tax relief will be popular with residents, but many of these same residents also prefer local autonomy. Any shift toward state funding (and away from local funding) would likely centralize, rather than decentralize, the decision making. In terms of an "income/property tax swap," the devil remains in the details, which still remain murky.