In January 2015, CMAP launched an interactive mobility data visualization website that allows users to explore metropolitan Chicago's regional system of roads, transit, and freight, which are not being adequately maintained. Resources to upgrade these assets are more scarce and precious than ever. This is the second in a series of Policy Updates that highlights CMAP efforts to address the region's mobility needs for greater economic prosperity and quality of life. This piece focuses on grade crossing delays.

The region's dense rail network plays a key role in moving both goods and passengers, but imposes costs on local communities. One key type of conflict occurs at the region's nearly 1,500 highway-rail grade crossings. Data from 2011 show that cars and trucks are delayed more than 7,800 hours each weekday at these locations, totaling more than 2 million hours of delay per year. While significant progress has been made in reducing delay through a variety of improvements -- such as crossing gates and signage, closing some crossings, and separating other crossings -- additional effort is needed to meet the region's goals as defined in GO TO 2040.

Safety and traffic operations

Grade crossings are an important planning topic for a number of reasons, not just motorist delay. Safety is a particular concern because rail operations are in direct conflict with highway, pedestrian, and bicycle traffic. Data on highway-rail grade crossings and related casualties are available from the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) and the Federal Railroad Administration, respectively. There were 283 collisions at public highway-rail grade crossings in the seven-county Chicago region between 2009-14, resulting in 65 fatalities and 146 injuries. Even in cases that do not result in serious injury or loss of life, crashes still have a high impact on delayed passenger and freight rail operations. An additional safety impact is the delay faced by emergency response vehicles at grade crossings. Finally, some freight trains transport hazardous materials, so the impacts of a potential crash could be devastating to local communities.

Grade crossings can also have significant impacts on local traffic operations. Perhaps the most visible impact is the "gate-down delay," or the backups caused when passing trains block the crossing. In addition, grade crossings can reduce both highway capacity and reliability. The uneven surfaces at grade crossings require vehicles to cross at low speeds, and passing trains preclude coordinating nearby traffic signals for more efficient operations.

Grade crossing delay

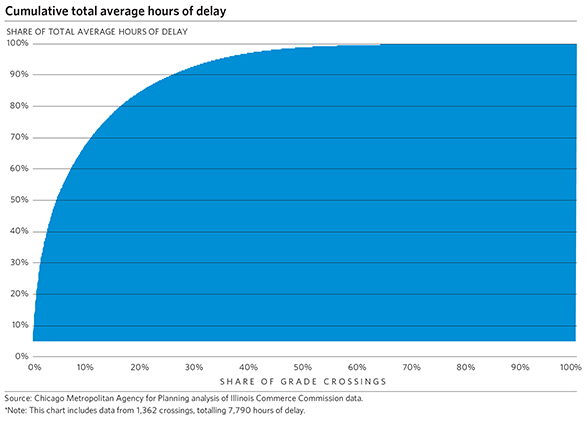

According to the ICC's 2011 report, average delay is highly concentrated among few grade crossings in the region. Out of roughly 1,500 crossings included in the report, the top 100 represented over 60 percent of the total delay. The top 10 locations, highlighted in CMAP's data visualization site, represented almost 20 percent of the total delay. The following chart demonstrates this concentration of average delay among relatively few highway-rail grade crossings in northeastern Illinois. The x-axis measures the percentage of grade crossings, sorted from the most delayed to the least delayed. The y-axis measures the cumulative average hours of delay. Only five percent of the region's grade crossings account for half the delay, and 10 percent of the grade crossings account for about two-thirds of the delay.

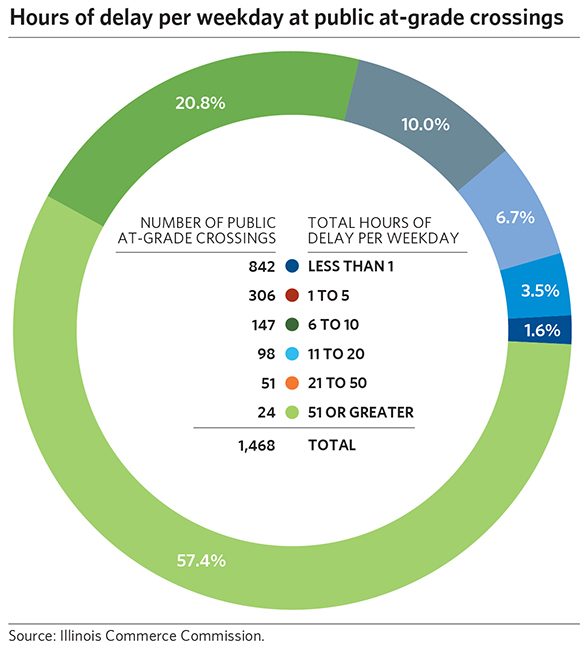

Put another way, the following chart shows that only 24 of the region's at-grade crossings experience more than 50 hours of delay, representing just 1.6 percent of the total number of crossings. In contrast, well over half (57.4 percent) of the region's crossings experience less than one hour of delay each day. These findings suggest that, by focusing on a relatively small subset of highway-rail grade crossings, regional planning efforts could achieve significant improvements.

Further, the ICC report demonstrates that grade crossing delay is disproportionately concentrated in the City of Chicago, which contains about 23 percent of all the region's crossings but 41 percent of the delay. Other municipalities with significant grade crossing delay are located in southern and western Cook County, along with a few others in north and northwest Cook County, DuPage County, and Will County. Together, these 20 cities accounted for 37.5 percent of crossings but 68 percent of the delay in northeastern Illinois.

Train operations can cause excessive gate-down delay, particularly near train yards and near rail-rail crossings. The amount of delay trains cause at any particular crossings varies, but in some cases exceeds an hour. Causes of this excessive delay vary from operational considerations to bottlenecks to equipment and facility problems. These delays can happen anywhere, but are not random and tend to be concentrated.

Grade crossing improvements

There are a number of potential safety improvements at rail crossings, from installing signage and warning devices to closing unnecessary crossings and consolidating traffic at safer, more reliable crossings. The ICC runs an active program of these crossing improvements across the state. Responsibilities for grade crossing maintenance and improvements are divided between the public and private sectors. Private railroads maintain the warning devices and crossing surfaces at the crossing, and public highway authorities maintain advance warning signs that are not on the railroad right-of-way. For more information on these and other rail issues, visit CMAP's Community Railroad Resources web page.

In some cases, the highway and rail lines can be separated entirely, moving the highway below or over the rail line. These highway-rail grade separations offer safety and operational benefits by entirely removing the point of conflict, but are expensive to build. As of 2015, 1,488 of the 2,969 public highway-rail crossings in the seven-county region, or slightly more than half of the crossings, have been separated, leaving 1,481 at grade.

Depending on the complexity of the project, grade separations can cost from about $10 million to over $100 million. While there are dedicated federal (Section 130) and state (Grade Crossing Protection Fund) funding sources for grade crossing improvements, these funds are limited and apply to different jurisdictions' roadways. General sources of federal, state, and local transportation funding can be also be applied, but grade crossing improvements must compete against a wide range of critical transportation needs. Private railroads are not typically required to pay all costs for highway-rail grade separations, although they often share costs.

It is important to note that changes to railroad operations may increase or decrease rail traffic at a crossing, affecting the need for or type of capital improvement. For example, changes to a railroad's network – such as purchasing or building new track, or abandoning old track – can allow service to be rerouted. As another example, demand for rail service can grow or diminish with the arrival or departure of industrial customers with direct access to rail sidings. These and other economic changes affect both the volume and location of rail traffic.

Illustrative projects

A number of grade separation projects have been completed recently or are underway throughout the region. Many of these are components of the Chicago Region Environmental and Transportation Efficiency (CREATE) program of rail improvements. Of the 25 grade separation projects included in CREATE, three have been completed (including Belmont Road in Downers Grove and 71st Street in Bridgeview), four are currently under construction (including 130th Street and Torrence Avenue in Chicago and Irving Park Road in Bensenville), six are in preliminary design, and the remaining 12 have not yet been started. Additionally, a number of non-CREATE grade separation projects are in design or under construction across the region, including several along the former Elgin, Joliet, and Eastern (EJ&E) Railroad at Rollins Road in Round Lake Beach, US 14 in Barrington, US 30 in Lynwood, US 34 in Aurora, and Washington Street in Grayslake.

Note, however, that alternatives to grade separations are often effective. Closing a poorly performing crossing is sometimes sensible. For example, CN worked with Joliet to close a crossing at Woodruff Road, near a rail yard, that had the highest number of excessive delays on the former EJ&E; CN helped fund a bypass to divert traffic to a better crossing. Likewise, CREATE projects to increase train speeds through the region may reduce delay at many affected crossings, even without crossing improvements.

Looking Ahead

CMAP's data visualization site demonstrates that much progress has been made in recent years, with average weekday delay at grade crossings falling from 11,000 hours in 2002 to 7,800 hours in 2011. This progress was driven by improvements such as grade separations, closing lines, rerouting service, and realignments. However, more progress must be made to meet the region's target of 5,500 hours of delay in 2040. Efforts like the improvements described above will contribute to this goal, but additional projects, and public and private funding sources to support them, must be identified. Additionally, excessive delay is an important issue in many parts of the region. While funding for capital improvements may help address excessive delays, railroad operations and federal regulations play a larger role. In fact, there has been recent legislative interest in addressing this issue, for example in the GROW AMERICA Act at the federal level and HB 420 at the state level. The performance of grade separations and other improvements, along with related policy issues, could be evaluated as part of the development of a regional freight plan, as called for by the Regional Freight Leadership Task Force.

GO TO 2040 calls on the region to create a more efficient freight network and identifies a number of specific implementation actions centered on the rail and highway systems. While those improvements embrace a number of capital and operational strategies, few tie together both rail and highway needs as directly as grade crossing improvements do. With broad implications for safety and traffic operations, and by extension to economic development and quality of life, grade crossing improvements are an important focus for regional planning.