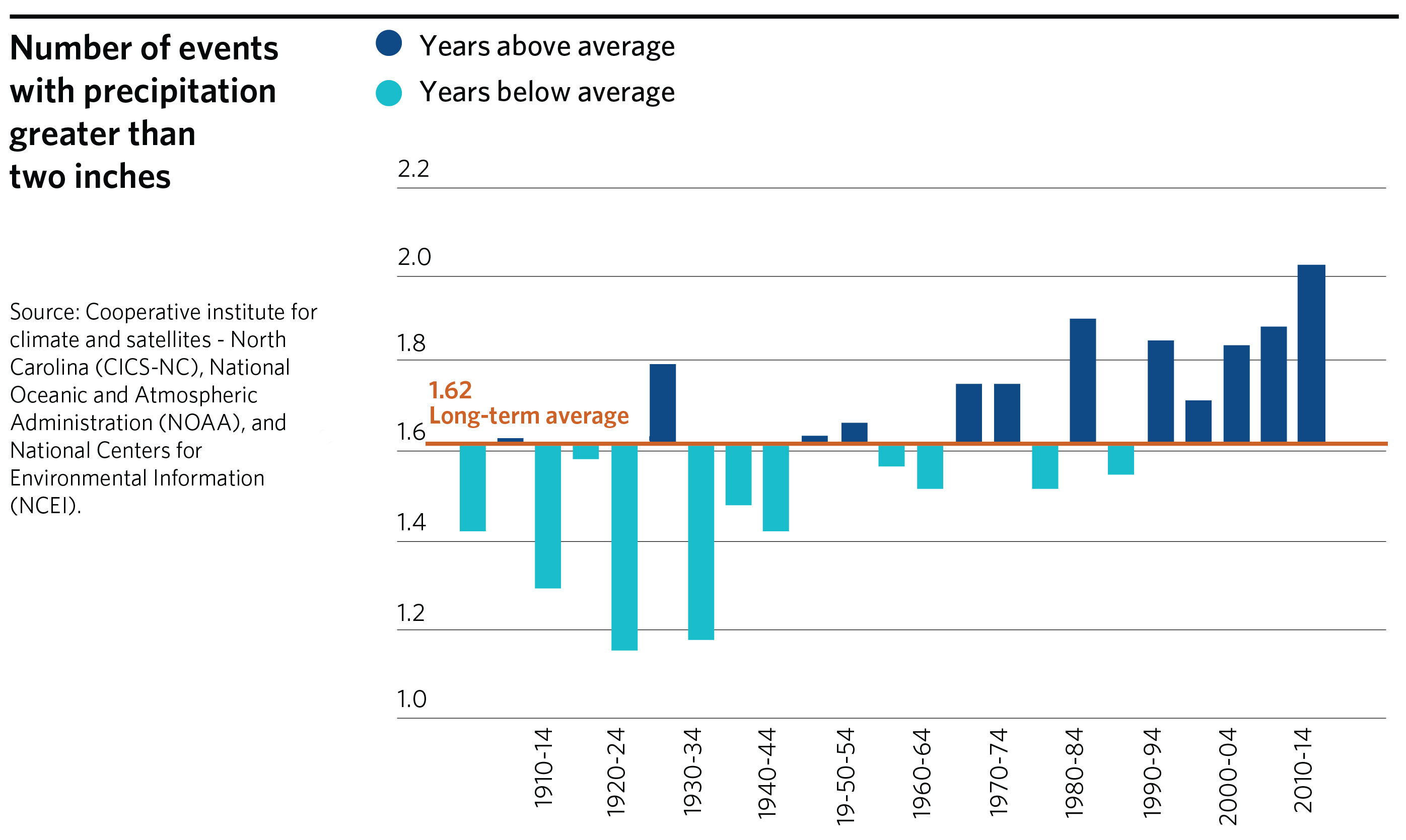

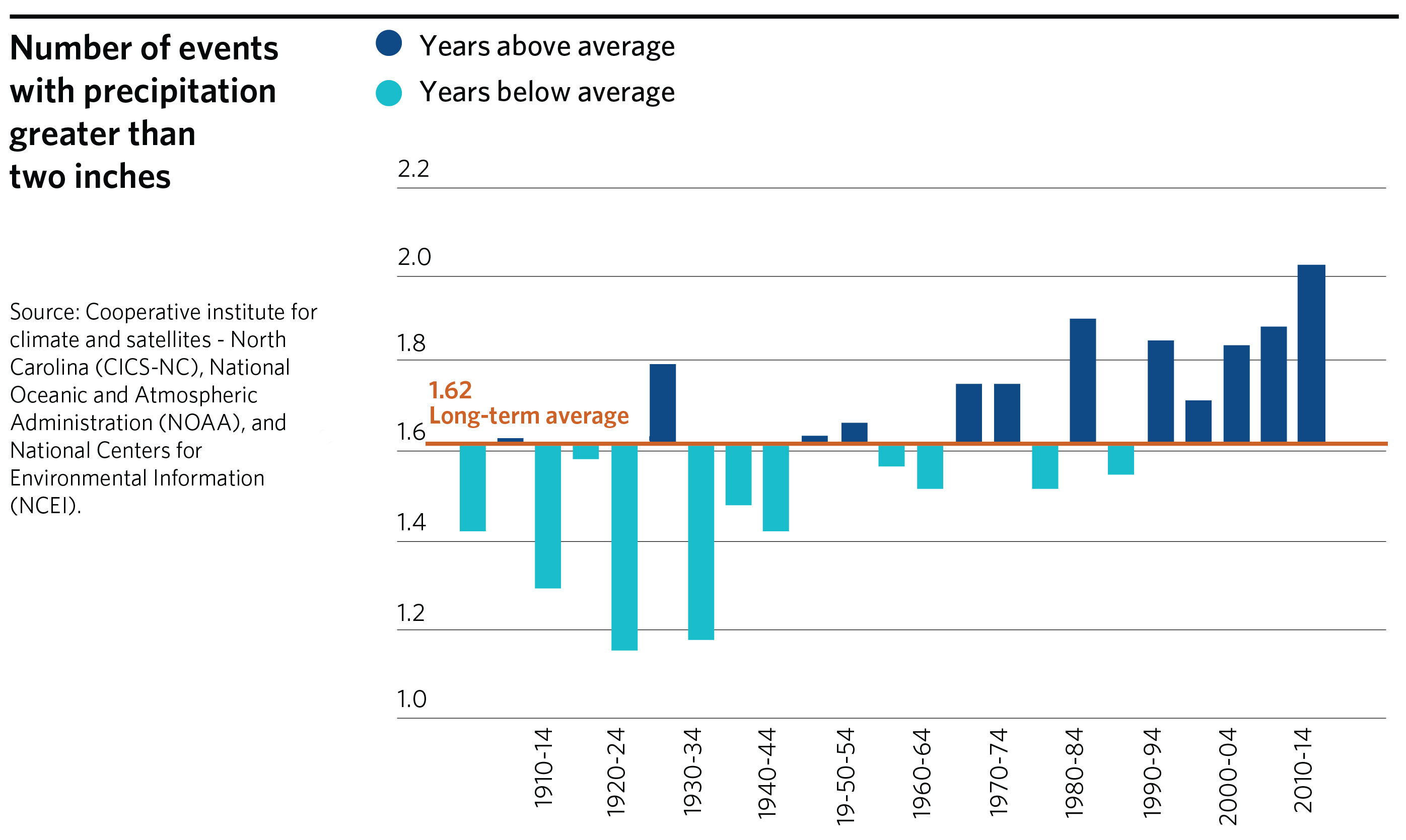

The region has seen its own share of historic weather events in 2020. The city of Chicago experienced the hottest summer, as well as the wettest May on record — setting a new high for the third year in a row. Heavy storms that month caused major floods across the region, particularly in communities along the Des Plaines River, such as Des Plaines and River Grove.

These events are part of larger, long-term changes in the region’s climate. In Illinois, the average annual temperature has increased by about 1 degree Fahrenheit since the beginning of the 20th century, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information. By the end of this century, temperatures in Illinois are expected to rise 7 to 12 degrees.

The region is already seeing the consequences. Flooding, in particular, is a serious and growing challenge for northeastern Illinois, with significant implications for our economy, ecosystems, residents, and built environment.

Currently, more than 450,000 properties in Illinois are at substantial risk of flooding, according to the First Street Foundation. The city of Chicago has the greatest number of at-risk properties in the state — and the second highest in the country — with 154,824 properties at any risk of flooding. By 2050, an additional 5,244 properties in Chicago are expected to be at risk.

Flooding causes property damage, threatens public health and safety, and impairs productivity. Many municipalities in the region are already contending with the effects of flooding, from major road closures to mold and sewer overflows, and disruptions to freight traffic. Flooding also has real economic costs for communities: Wet basements can decrease property values by 10 to 25 percent, according to the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT). And the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has found that 40 percent of small businesses never reopen after a flooding disaster.

Flooding — and other impacts of climate change — also tend to disproportionally affect low-income and other vulnerable communities. A CMAP analysis found that economically disconnected areas (EDAs), or communities disconnected from the region’s economic progress, are more likely to be in flood-susceptible locations. A contributing factor could be that disadvantaged communities often have older infrastructure and limited resources to maintain an infrastructure replacement program. In the city of Chicago, 87 percent of flood damage insurance claims were paid in communities of color, according to CNT.

After a particularly wet May, flooding may be top of mind for many local governments. But it’s far from the only impact of climate change. Heat waves have caused illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths in vulnerable communities, and drought has had significant adverse effects on the region’s agricultural sector and natural areas. Communities across the region will face different climate challenges. For example, extreme rainfall is the most significant climate threat in Cook County, while water stress is the top threat for Kane County, according to an interactive graphic from The New York Times. Water stress occurs when the demand for water exceeds the available supply, either due to over-consumption or drought conditions.

The Chicago region will likely face increased challenges going forward. For example, warming winters can lead to more freeze-thaw cycles, which cause more rapid deterioration of roads and other infrastructure. And as the climate warms, populations from regions more severely harmed by climate change — such as the southern and coastal U.S. — may migrate to northeastern Illinois. That will have new implications for our economy, natural resources, and infrastructure.