As the charts above indicate, commute times and distances changed minimally from 2003-13. Overall, commute time and distance for freight and manufacturing workers are similar to regional averages, with a slightly shorter commute time and distance for the region's manufacturing workers. As of 2013 more than three-fourths of the region's workers spend less than 60 minutes commuting one way. In terms of distance, about 80 percent of the region's workers commute less than 30 miles one way with more than half commuting less than 15 miles.

Commute time and distance has recalibrated to changing levels of regional freight and manufacturing employment. According to LEHD data, manufacturing employment, currently at over 355,000 jobs, declined by 21 percent between 2003-13. This aligns with prior CMAP analysis of the region's changing

manufacturing cluster. This reduction in the manufacturing workforce led to commensurate reductions in manufacturing commuters, although proportions in each time and distance category remained similar. Regional freight employment has increased 11 percent from over 150,000 in 2003 to over 168,000 in 2013. As the level of freight employment has increased, these workers are traveling slightly longer distances and times.

With a changing employment landscape, some of the region's commuters are traveling longer times and distances to get to work. Nearly 40,000 freight and manufacturing workers and over 80,000 workers in the "all other jobs" category travel 90 or more minutes to work one way, spending at least 10 more hours commuting per week than the average commuter in the CMAP region. These workers spend the equivalent of almost 21 entire days commuting over the course of one year.

Between 2003-13, the percentage of manufacturing workers with long commutes, defined as driving over 90 minutes and commutes more than 60 miles, decreased, while the region's longest commutes increased for freight and all other workers. These commute trends may be partially attributed to merging patterns in locations of residence and employment for manufacturing workers. Conversely, freight commute patterns may indicate that an increasing share of freight workers are living farther away from their jobs and spending more of their time commuting compared to ten years prior.

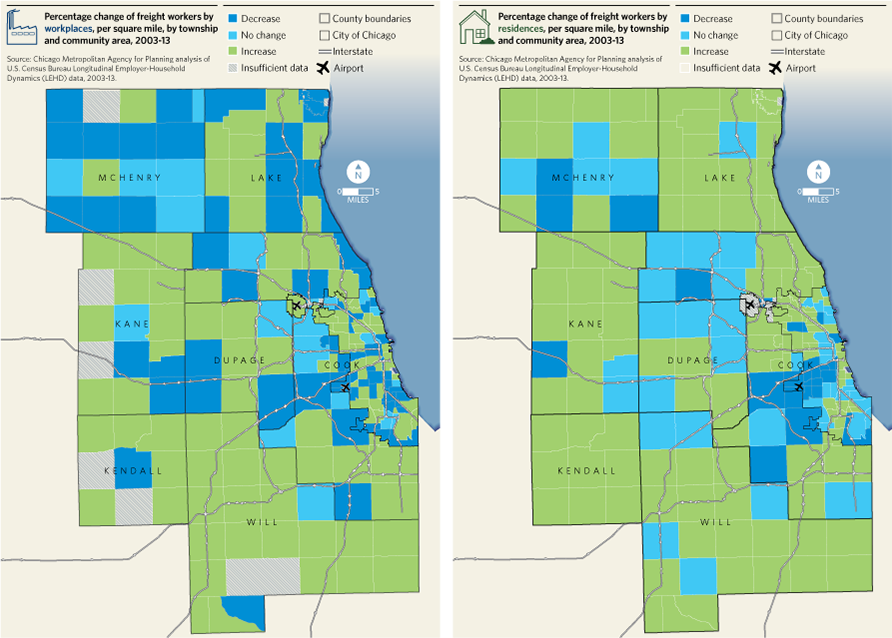

While freight employment occurs throughout the region, freight jobs are becoming increasingly concentrated along major transportation corridors in the City of Chicago, and the counties of Cook, DuPage, and Will -- areas with high access to highways, airports, and rail. Areas of the region with longstanding freight employment concentrations, including communities adjacent to O'Hare Airport and Chicago's Loop, have also experienced growth in freight jobs from 2003-13.

The number of freight workers by place of residence has increased substantially throughout the region. Will County in particular has seen growth in residents employed in the freight industry, paralleling the increase in freight employment in this area. Community areas on Chicago's southwest side and municipalities in southwest suburban Cook County adjacent to Midway Airport have experienced a decrease in residents employed in the freight industry.

Commute time and distance for freight workers have increased slightly from 2003-13, mirroring commute patterns for all other jobs in the region. Over the same period, the freight industry employment grew 11 percent.

Manufacturing

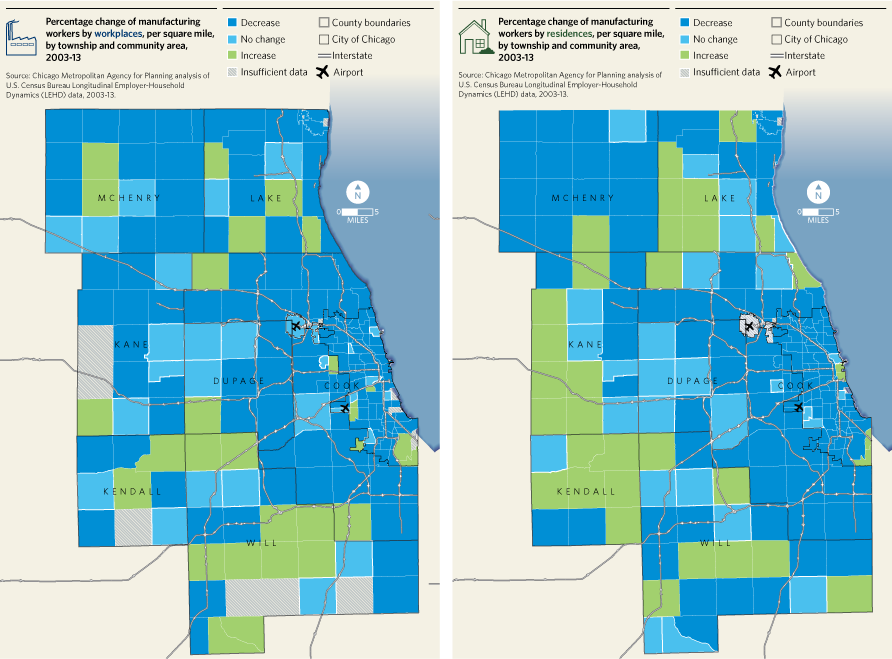

The maps below illustrate that manufacturing employment, while declining overall, has grown outside the region's urban core. Areas of the region with historically strong manufacturing employment, such as north suburban Cook County and northeastern DuPage County proximate to O'Hare Airport, have seen manufacturing employment loss since 2003. Generally, manufacturing employment loss in this area is in line with greater regional trends of manufacturing job loss.

South suburban Cook County has experienced some of the most significant loss in manufacturing workers. Several factors could contribute to this trend, including loss of manufacturing jobs in the region overall, pressure to transition to higher-value development types, or increased congestion in the region's core.

Some townships in Will and Lake have seen modest increases in manufacturing employment. In Lake County, some areas along Interstate 94 have seen an increase in manufacturing workers. Between 2003-13, Will County also experienced growth in manufacturing employment, particularly near highways and intermodal facilities. Not all growth in manufacturing employment has occurred in suburban areas of the region; the City of Chicago has seen growth in manufacturing employment in some areas of the southwest and south sides of the city.

Economic and land use trends also shape the location of the region's freight and manufacturing facilities. Modern warehouses, distribution centers, and manufacturing facilities may require larger buildings. Lower margins may necessitate development on less expensive parcels farther from the region's urban core. Locating these facilities in densely

developed areas is more challenging due to the need to assemble small parcels of land with a multitude of owners,

brownfield remediation, and regulatory restrictions.

While some of the region's freight and manufacturing hubs remain healthy or have been

converted to other uses, others struggle to attract reinvestment, leading to an increase in underutilized

industrial land in the region's urban core.

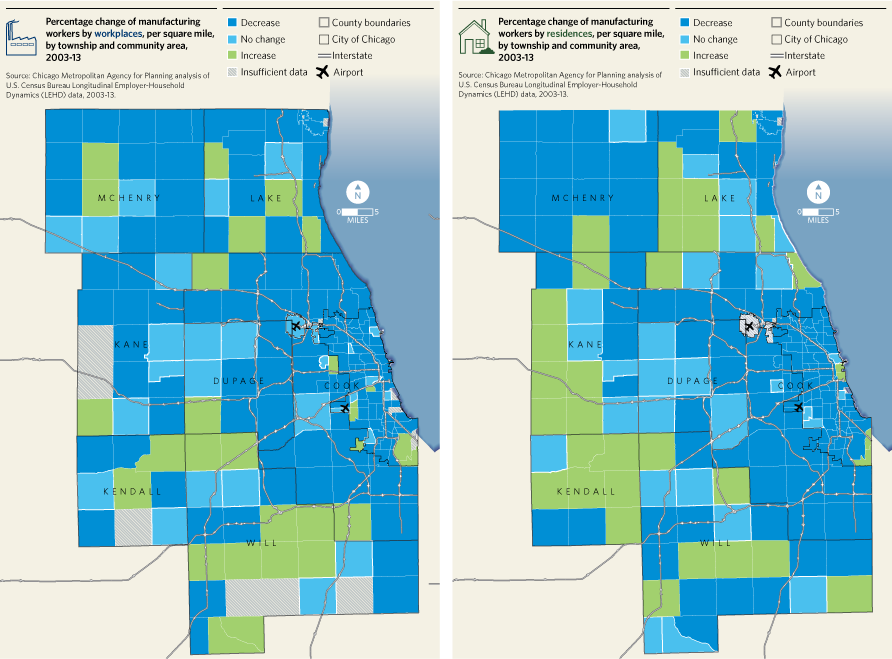

Following broader regional suburban expansion, the number of residents employed in manufacturing has increased at the edge of the region, as indicated on the map above. In sync with greater regional population growth, Kane, Kendall, and Will counties have experienced an increase in the number of manufacturing workers living in these counties.

Some areas of Cook County, including in the City of Chicago have had growth in residents employed in manufacturing. Some north suburbs have also seen growth in residents employed in manufacturing, even in areas with relatively flat population growth. These increases are paired with growth in manufacturing jobs in these areas.

At the same time, the City of Chicago and Cook County have seen some of the most substantial losses in the number of residents employed in manufacturing from 2003-13. In particular, community areas on the city's west side have experienced some of the most significant loss of residents employed in manufacturing. This decrease may be attributed to

population loss, or the changing demographic compositions of these areas.

One potential explanation for manufacturing workers' relatively constant commute time and distance may be that the region's manufacturing labor supply may be moving as the location of employers shifts.

Looking ahead

As GO TO 2040 indicates, during the last several decades, metropolitan Chicago's population has shifted outward from the region's core. Despite this movement, commute time and distance for the region's freight and manufacturing workers changed minimally between 2003-13. Targeting future freight and manufacturing development toward already-developed areas can leverage existing transportation and infrastructure assets and also better connect jobs to where workers reside.

However, larger issues that affect commuting, such as land use, transportation, and congestion, may hinder regional economic growth due to decreased mobility over time. Congestion not only directly affects the freight and manufacturing clusters by

increasing costs for firms and reducing reliability for shipments, it also hampers the access and productivity of its workforce. GO TO 2040 recommends strategies to address the

mismatch of jobs to housing, such as reinvesting in existing areas, moderately increasing density near transit, investing in transit facilities, and promoting a well-balanced housing supply. These efforts help improve our economy and quality of life by giving people more choices for getting around, working, and living.