Establishing water quality standards for nutrients has major implications for the investments society makes in treating sewage and cleaning up rivers. The federal Clean Water Act requires that states set water quality standards (described for Illinois online) to protect the "beneficial uses" of streams and lakes, such as for supplying public water or supporting aquatic life. Like many other states, however, Illinois is well behind the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (U.S. EPA) deadline for each state to develop its own numeric nutrient standards. A lack of nutrient standards in Illinois actually transcends state borders and can negatively impact waters as far away as the Gulf of Mexico. With the setting of nutrient standards comes the additional expenses of nutrient removal, and Illinois will need a flexible approach with creative solutions, such as allowing industry or publicly owned wastewater plants to offset their nutrient contributions with other projects downstream, to achieve nutrient standards in a cost-efficient manner.

It is important to understand how numeric standards work. Say there's an obviously dangerous chemical called dimethyl terrible. To protect aquatic life, Illinois might determine that, based on laboratory experiments, dimethyl terrible in streams and rivers should never be more than 0.15 milligrams per liter (mg/L) at any time, or more than 0.10 mg/L on a long-term basis. If a stream is found to exceed those standards, it should trigger efforts by the state to correct the problem and may influence the allowable quantity of the chemical discharged by industry or publicly owned wastewater plants. Unfortunately, other pollutants in water, such as excessive sediment, prove more difficult to quantify and standardize. Rivers are essentially eroding the land all the time -- indeed, that's how rivers form -- carrying this sediment downstream. Since rivers carry some sediment naturally, how much is too much?

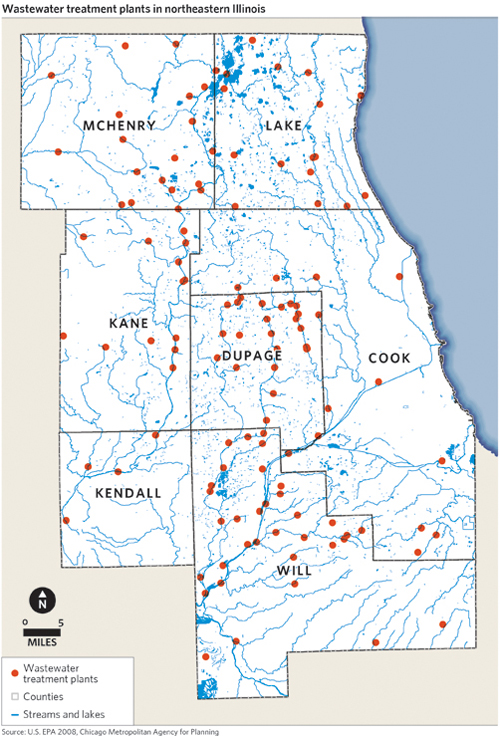

Nutrients are similar. Nitrogen and phosphorus, collectively called "nutrients," cycle naturally between the atmosphere, soil, water, and living things. Aquatic plants need them in order to live, as do the organisms that rely on plants for food and cover. But much higher levels of nutrients do enter some streams both from nearby farm fields (where fertilizer may be applied intensively) and from wastewater treatment plants (of which there are about 140 in the Chicago region). Other sources of high nutrient levels include pets and residential fertilizer used in developed areas.

In lakes, excessive nutrients can lead to algal blooms and large "mats" of slimy algae in streams. High concentrations of nutrients in drinking water can threaten human health. In fact, nutrients are thought to be degrading many streams and lakes in Illinois. Phosphorus is usually one of the ten most widespread problems identified in the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency's biennial report on water quality conditions (see the chart below). Because of these problems, CMAP often addresses nutrient pollution in the watershed plans that our agency develops. Nutrient loading is also examined as part of CMAP's Facility Planning Area process.

Partly due to the difficulty of setting numeric nutrient standards, Illinois, like many other states, still hasn't set any, with the exception of total phosphorus in lakes and streams leading into larger lakes. Thus, while Illinois has identified nutrients as a cause of water quality problems, planners and engineers cannot really say by how much these nutrients need to be reduced. In fact, the U.S. EPA originally issued a directive for the states to develop numeric nutrient standards by 2004. Those deadlines have come and gone, but pressure from the federal government and environmental advocates continues. Last summer Wisconsin adopted nutrient standards for lakes and streams, a decision that came after environmental groups had threatened to sue the state to issue rules on nutrients. In Florida, the federal government itself developed the state's nutrient standards, which were finalized in Novemberafter the state was sued by environmental groups to compel it to do so. It seems likely that nutrient standards will have to be developed in Illinois in the not-too-distant future.

Originally, the federal government had suggested several methods, among which states were to choose in setting standards. Starting in 2003, Illinois opted to conduct research -- primarily by researchers affiliated with the Council on Food and Agricultural Research in Champaign -- to try establishing cause-and-effect relationships between nutrient levels and degraded conditions in the state's streams. Some of the research is described in presentations from the September 2010 "Nutrient Summit" held in Springfield. Unfortunately, this research has not been completely conclusive, as many other factors come into play. For example, aquatic life is also affected by the quality of stream habitat, which is poor in streams affected by years of agricultural drainage practices followed by urban development. The Illinois Association of Wastewater Agencies, an industry group, argues that trying to remove excess nutrients from a stream might not help fish and aquatic bugs much. It says improving habitat or addressing other "stressors" in those streams would be more important than removing nutrients. The group suggests that nutrient removal would only be justified if it could clearly be shown to improve biological conditions.

But benefits to Illinois streams are perhaps not the only consideration. The Gulf of Mexico has a large "dead zone" devoid of most marine life near where the Mississippi River empties into the Gulf. It's caused by the accumulated nutrients from many cities, farms, and industries across the Midwest, including those in the Chicago region. As nutrient concentrations build, algal growth skyrockets and the ensuing die-off of the algae consumes oxygen rapidly, leading to very low oxygen conditions. Interestingly, the nutrient standards Illinois is developing are not aimed at attacking this dead zone, but in improving local stream conditions. Instead, the federal government and ten states are undertaking a separate process to combat the dead zone through the Mississippi River Basin Watershed Nutrient Task Force, which has been working on the issue since the late 1990s.

It is worth pointing out that, while most of the nutrients at the scale of the Mississippi basin seem to be coming from agricultural operations (although wastewater is still a significant contributor), farming is mostly unregulated under the Clean Water Act. In other words, nutrient standards adopted by the states won't do much to move farmers toward adopting practices to reduce nitrogen and phosphorus loss from their fields, which can be fairly inexpensive. On the other hand, the standards would lead to expenditures, generally by the public, to upgrade wastewater treatment plants, which can be pricey.

These cost differences between the available approaches to nutrient removal has led to consideration of potential trading between sources.For example, if a treatment plant needed to remove X amount of phosphorus, but there were farmers nearby who could obtain the same reductions more cheaply, then why not pay the farmers to do it? Trading schemes can be complex, but they hold potential. Taking this a few steps further is the approach of the local Wetlands Initiative, which promotes a system whereby farmers with land in the Illinois River floodplain can restore wetlands there and be paid to do so by those who are discharging nutrients upstream. The wetlands these "nutrient farmers" create, generally on marginal farmland, would remove nitrogen and phosphorus from the river and might make the farmers more money than if the land were farmed.

Such a program does not exist yet in Illinois. The state would have to require dischargers to remove nutrients or buy nutrient credits sold by farmers, and an exchange would need to be set up to facilitate the sale and purchase of these credits. Given the success of such trading programs in reducing the cost of meeting air quality standards, there has been much interest in using them to improve water quality, and successful examples do exist.

But trading is not necessarily the only way to lower the costs of nutrient removal. The Water 2050 regional water supply/demand planrecommends using treated wastewater for irrigation (generally of turf grass in golf courses), which would reduce the amount of nutrients running off into streams and cut the cost of applying fertilizer. Hopefully, the expected costs of nutrient removal will lead to more creative thinking about how to achieve nutrient standards once they are adopted in Illinois, but it will require a flexible approach to regulation by the state.