This is the final Policy Update in a four-part series on public-private partnerships (PPPs). The first two defined PPPs and discussed their role in the ongoing federal transportation reauthorization process. The third discussed policy issues related to PPPs and transit projects.

In 2011, the Public-Private Partnerships for Transportation Act (HB 1091) was signed into law. It provides broad authority for the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) and Illinois Tollway to enter into PPP agreements. Given this new authority, this Policy Update assesses the potential to develop major capital projects in the region using innovative delivery methods.

Existing PPPs in the Region

Recent examples of PPPs in the greater Chicago region have granted long-term leases of existing transportation facilities to private consortia, including the Chicago Skyway and Indiana Toll Road. Note that a long-term lease or concession represents one example of a PPP agreement; other contractual arrangements may provide for a more limited private role. These two regional examples are briefly profiled below, and more information on each can be found in reports from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) and U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Chicago Skyway

The Chicago Skyway is a 7.8-mile elevated segment of Interstate 90 that links the Dan Ryan Expressway (I-90/94) to the Indiana Toll Road (I-90) on the south side of Chicago. The City of Chicago accepted a $1.83 billion, 99-year lease offer from the Cintra-Macquarie consortium in October 2004. The original deal included equity from both Cintra and Macquarie, as well as $1 billion in bank loans.

The deal awarded operations and maintenance responsibilities to the private consortium, as well as all toll revenues for the concession period. In addition to requiring the private partners to make certain capital improvements (e.g., installation of electronic tolling equipment), the contract restricts toll rate increases to no more than 50 cents each year from 2008 to 2017 (i.e., a cumulative increase from $2.50 to $5.00). After 2017, the maximum rate of increase per year is limited to the larger of two percent, the growth in per capita gross domestic product (GDP), or the consumer price index (CPI).

According to a 2010 financial report, one of the private concessionaires (Macquarie Atlas Roads), earned $13.5 million in revenues against $1.95 million in expenses on the Chicago Skyway, leading to an EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) margin of 86 percent.

Indiana Toll Road

The Indiana Toll Road is a 157-mile segment of Interstate 80/90 in northern Indiana from the Illinois border to the Ohio state line. In October 2005, the Indiana Finance Authority selected a $3.8 billion, 75-year bid made by the Indiana Toll Road Concession Company LLC, also a partnership of Cintra and Macquarie. Each partner contributed $385 million in equity, with seven European banks providing the remaining $3 billion in loans. The private concessionaire assumed full operations in June 2006.

The lease agreement limited toll rates to $8 through June 2010, while capping subsequent annual toll rate increases to the greater of two percent, the growth in per capita nominal GDP, or the growth in CPI. The State of Indiana used the concession payment to fund a ten-year, $10 billion transportation capital program, Major Moves, which includes the construction of I-69 between Indianapolis and Evansville. The State also used the proceeds to fund $150 million in transportation projects statewide over two years, as well as projects specifically in the toll road region. The concession agreement does contain a non-compete provision, which prohibits the State from constructing new highway facilities of at least ten continuous miles in length within 20 miles of the Indiana Toll Road.

According to the 2010 financial report, Macquarie Atlas Roads earned $43.9 million in revenues against $8.4 million in expenses on the Indiana Toll Road, leading to an EBITDA margin of 81 percent.

GO TO 2040 Major Capital Projects

CMAP's GO TO 2040 regional plan recommends a small number of major capital projects. This Policy Update analyzes four new projects or major extensions and two managed lanes projects, just a few of the plan's priority projects. It identifies and summarizes comparable PPPs from across the country based largely on land use, demographic, and facility design factors. These comparisons are done at a high level and are meant as illustrative only. The projects included in this analysis are:

- Elgin O'Hare Expressway and West O'Hare Bypass

- Central Lake County Corridor (IL-53/120)

- I-55 Managed Lanes

- I-90 Managed Lanes

- West Loop Transportation Center

- CTA South Red Line Extension

Comparable Facilities

CMAP staff identified comparable projects from the Public Works Financing U.S. Transportation Projects Scorecard (October 2011: pp. 22 to 24) and the Federal Highway Administration's PPP Project Profiles. Staff considered variables such as a facility's type, length, cost, land use context, and location in selecting comparable projects.

New Highway Facilities: Elgin O'Hare West Bypass and Central Lake County Corridor

There are several examples in the U.S. of new toll roads developed as PPPs, the majority of which have been executed as design-build (DB) agreements in which the same private entity is responsible for designing and constructing the facility. Examples include the Foothill and San Joaquin Hills Toll Roads in Orange County, CA; State Highway 130 Segments 1 to 4 in Austin, TX; E-470 in Denver, CO; and the Intercounty Connector in Maryland.

In other cases, the private sector takes more responsibility, including the financing, operation, and maintenance (DBFOM) of the facility. Examples include the Dulles Greenway in northern Virginia; South Bay Expressway in San Diego, CA; State Highway 130 Segments 5 to 6 in Austin, TX; Pocahontas Parkway in Richmond, VA; Northwest Parkway in Denver, CO; Camino Colombia Bypass in Laredo, TX; and the State Route 91 Express Lanes in Orange County, CA. Some of these facilities were initially designed, financed, and constructed by private entities but later sold to public owners (e.g., South Bay Expressway, SR 91 Express Lanes), while others were built and financed by the public sector but later leased to private consortia (e.g., Pocahontas Parkway, Northwest Parkway).

Elgin O'Hare West Bypass

None of the examples profiled here is directly comparable to the Elgin O'Hare West Bypass project. While other facilities are similar in length to the Elgin O'Hare West Bypass (11 miles) -- including the Pocahontas Parkway (9 miles), South Bay Expressway (10 miles), Dulles Greenway (14 miles), and San Joaquin Toll Road (14 miles) -- and also provide access to major airports (e.g., Dulles Greenway and E-470), no project is located in a largely built-out, heavily-industrial context.

In relation to the larger expressway network, the Elgin O'Hare project would fill in subregional gaps, extending an existing freeway and bypassing O'Hare Airport. In contrast, the Northwest Parkway and E-470 are components of a metropolitan beltway, the Intercounty Connector also acts as something of an outer beltway, and the SH 130 projects essentially comprise a large bypass of I-35 in Austin, TX.

Central Lake County Corridor

The Central Lake County Corridor (IL-53/120) project has somewhat reasonable comparators, including the San Joaquin Hills and Foothills/Eastern Toll Roads. To some extent, each acts to bypass a long-distance, high-volume route (I-405 and I-5) and travel through suburban residential areas interspersed with nature preserves. As such, the toll roads are similar to the IL-53/120 project's relationship with I-94 and environmentally sensitive areas. Orange and Lake Counties also have relatively similar median household incomes: $71,735 and $76,336 in 2009, respectively.

The Dulles Greenway and Intercounty Connectors are also located in wealthy suburban counties. The median household income of Loudoun County, VA, where the Dulles Greenway is located, was $114,200 in 2009, and the median household income in Montgomery County and Prince George's Counties, MD were $93,774 and $69,545, respectively. The three counties are largely residential and have large amounts of open space, including agricultural land in Loudoun County. The Dulles Greenway acts as an extension of the Dulles Toll Road and parallels VA-7, similar to the IL-53 extension and its relationship with I-94. The Intercounty Connector parallels I-495 and connects two other interstate highways: I-270 and I-95.

The South Bay Expressway in San Diego provides an extension of SR-125 and parallels larger-volume I-805 and I-5 to the west. The South Bay Expressway passes through suburban residential areas, as well as large open space areas. The Olympic Parkway toward the southern end of the facility is a large arterial that connects the South Bay Expressway to I-805. The Olympic Parkway may be comparable to the proposed IL-120 bypass: it has relatively few intersections, provides four lanes of traffic with a planted boulevard, and contains a bicycle and pedestrian path.

All of the IL-53/120 comparators are roughly similar in length, with the exception of the Foothill/Eastern Toll Road (34 miles) and Intercounty Connector (18 miles).

Financial Success of Comparators

The construction of a new toll is an inherently risky endeavor: traffic levels must be projected with accuracy many years into the future, and the financial underpinning of a project is based on these projections. As this NCHRP reportdemonstrates, many new toll roads built in the past few decades experienced far lower traffic volumes than projected, including PPP examples such as the Northwest Parkway, Pocahontas Parkway, E-470, San Joaquin Hills Toll Road, Foothills Toll Road (north), and Dulles Greenway.

For projects in which a private partner is responsible for financing a new road, lower-than-expected traffic volumes can lead to severe financial problems and, in the case of the Camino Colombia and South Bay Expressway, bankruptcy. Public agencies are not immune from forecasting errors: the Pocahontas Parkway had been built by the Commonwealth of Virginia, but was leased to a private entity after traffic volumes were lower than anticipated. Similarly, the Northwest Parkway was leased to a private entity in order to avoid default. According to the private concessionaire Transurban, the Pocahontas Parkway earned $14.1 million in revenue for the year ending June 30, 2011, an increase of 2.4 percent.

Several of these projects were recipients of federal credit assistance through the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, including the Intercounty Connector, South Bay Expressway, and the Pocahontas Parkway.

Improvements to Existing Highway Facilities: I-55 and I-90 Managed Lanes

Rather than constructing new, greenfield facilities, other highway PPP agreements provide for the reconstruction and widening of existing highways. These additional lanes are often built as managed toll lanes. A managed lane uses multiple operational strategies to achieve pre-defined performance objectives. Managed lanes often use variable toll rates to ensure reliable, fast travel speeds. The toll revenue can be used to directly or indirectly reimburse the private sector and provide reasonable rates of return to investors. Examples include the I-635/LBJ Freeway Managed Lanes project in Dallas, TX; the North Tarrant Express project in Fort Worth, TX; the DFW Connector project in Fort Worth, TX; the I-595 Express Lanes project in Fort Lauderdale, FL; and the I-495 High Occupancy Toll (HOT) Lanesproject in northern Virginia.

To some extent, all five projects profiled here are apt comparators for the I-90 and I-55 managed lanes proposals identified in GO TO 2040. All examples are located in congested corridors in large metropolitan areas. All involve the construction of new managed lanes, often in tandem with the reconstruction of the mainline facility. All are located in a variety of land use contexts, including industrial, residential, and commercial/retail. Two examples, the DFW Connector and North Tarrant Express, provide access to a major airport (Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport), as do I-90 (O'Hare International Airport) and I-55 (Chicago Midway Airport).

However, these projects are broader in scope than the two proposals for northeastern Illinois. The DFW Connector, I-495 HOT lanes, and North Tarrant Express projects will each provide four new managed lanes (two in each direction), I-595 will provide three reversible lanes, and I-635/LBJ will provide between four and six managed lanes (two or three in each direction). The I-90 and I-55 projects, on the other hand, would involve two new managed lanes (one in each direction). The I-636/LBJ project is perhaps the most complex; it plans to provide elevated or subsurface lanes for most of the route and construct dedicated connector ramps. These projects are mostly DBFOM agreements, which assign a high level of responsibility to the private partner. Only one example, the DFW Connector, employs a more limited DB arrangement.

Legal Issues -- PPP and Highway Facilities

Under current law, the Illinois Tollway would not be allowed to enter a DBFOM agreement on I-90. According to the state's enabling legislation for PPPs, HB 1091, the Tollway may not "enter into a public-private agreement for the purpose of making roadway improvements, including but not limited to reconstruction, adding lanes, and adding ramps, to any toll highway, or portions thereof, under the Authority's jurisdiction which were open to vehicular traffic on the effective date of this Act" (Section 15b). However, a bill filed in February in the Illinois House of Representatives, HB 4502, would strike this language. The Tollway or IDOT would be allowed to enter into a PPP for a new facility such as the Central Lake County Corridor.

Financial Success of Comparators

It is difficult to determine the financial success of most of these comparable examples; only the SR 91 Express Lanes are currently operational. According to the 91 Express Lanes Annual Report for FY2010 to 2011, the lanes have maintained an "A" bond rating every year since 2003. The lanes earned $41.2 million in operating revenues and spent $22.4 million in operating expenses for the one-year period.

Several of these projects were recipients of federal credit assistance through the TIFIA program, including I-635/LBJ Managed Lanes, North Tarrant Express, and the I-495 HOT lanes.

Transit Facilities: West Loop Transportation Center and CTA South Red Line Extension

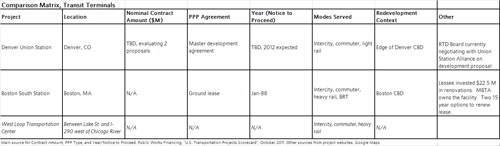

There are several examples of DB agreements for transit projects, but there are fewer examples in which the private sector assumes more extensive roles as designer, contractor, manager, operator, and financier. Examples of transit PPP agreements include the Hudson-Bergen light rail line in New Jersey; the Hiawatha Light Rail Transit in Minneapolis, MN; the EAGLE commuter rail project in Denver, CO; the Denver Union Station redevelopment in Denver, CO; the Oakland Airport Connector in Oakland, CA; the Boston South Station renovations; and the Portland MAX Airport Extension. The only fully-privatized transit project in recent years is the Las Vegas Monorail in Las Vegas, NV.

Additionally, value capture can be considered to be a form of PPP. Transit investments, and transportation investments more generally, often increase the value of adjacent property. Value capture uses taxation to capture some of this value in order to fund the original transportation facility. CMAP has issued analysis on the use of value capture for transportation projects in the Chicago region, as well as specifically for transit.

None of the case studies profiled here include a new heavy rail line, such as the proposed Red Line Extension. Rather, the Hudson-Bergen, Hiawatha, and Portland MAX Airport Extension lines are light rail facilities, the Las Vegas example is a monorail, the Oakland Airport Connector is an automated guideway transit project, and the Denver EAGLE project will deliver two new commuter rail lines. The modal diversity of these case studies suggests that a public-private agreement could be adapted to suit a heavy rail project.

These examples are generally entirely new facilities, rather than incremental additions to existing facilities. Although they are new facilities, the Hudson-Bergen and EAGLE projects do interface with existing rail transit in their regions.

In contrast, two of the examples are extensions to existing transit systems; interestingly, both are extensions to serve airports. The Portland MAX Extension PPP agreement was a DB project, with the private party also contributing about 25 percent of the project's cost in exchange for development rights on 120 acres of property owned by the Port of Portland. The Oakland Airport Connector will connect to Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) and will be considered a component of the BART system, but will be operated by a private concessionaire and represent a different mode than the larger BART system.

The terminal projects share some similarities with the West Loop Transportation Center project. For example, they all serve multiple modes of transit and are located in central business districts. However, they do not all share the project's complexity. The West Loop Transportation Center would also involve engineering challenges due to its vertical profile and extensive tunneling, and it would also require the construction of new subways.

The Boston South Station example is a fairly limited PPP that provides for renovations of an existing facility and the ongoing management of its tenants. The Denver Union Station example is more comprehensive project, including redevelopment of the adjacent neighborhood and the incorporation of new rail lines. The special-purpose Denver Union Station Project Authority is responsible for the financing, design, construction, operations, maintenance, and ownership of the redevelopment project.

Financial Success of Comparators

It is difficult to determine the financial success of a transit PPP project. The examples profiled here generally do not provide for private financing of projects, and those that do, including the Denver EAGLE project and Denver Union Station, are currently under construction and will not be operational for some years. In the Portland MAX case, the project's financial success is intertwined with real estate development, the data for which is not readily available.

The Denver Union Station and EAGLE projects were recipients of federal credit assistance through the TIFIA program.